10Politics is downstream from culture.

This has become a popular turn of phrase in conservative and libertarian circles. And, by all means, there’s certainly a lot of truth to it. But, I think it misses an incredibly important point. It’s a mistake to treat culture itself as an entirely exogenous variable. Culture doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Culture itself is shaped and altered by policy, and consequently politics. That is to say, if politics is downstream from culture, it’s also a tributary into the culture.

But, how do politics shape culture, you might ask. Well, you first have to consider the nature of what is culture. Culture is the manifestation of the social beliefs, values, conventions and tastes shared by a group of people. But, all of those things happen in the context of the success they produce for those who practice them. A great many, if not all, cultural traits arise because they work. They provide a practical advantage in the conditions in which they are adopted. In fact, they very well may become elements of the culture precisely because they provide such advantages. Success breeds imitation and imitation breeds institutionalization. To the point that the initial advantage may well be beside the point. But those conditions are hugely affected by the politics prevalent in the society in which they are adopted.

As just one example, you see longstanding reputations for a poor work ethic for certain cultures. Why would that be? I’m not saying that it’s not just the random interplay of luck or providence with certainty. But, you find a remarkable correlation of those cultures regarded as having poor work ethics and those cultures with high levels of official predation. For the libertarian, this relationship should be obvious. If the consequence of your busting your behind is just going to be that the guy with the club bashes you over the head and takes your stuff, busting your butt is a suckers’ game. It’s not surprising, then, that you don’t see work elevated to a particularly high status in those societies.

All of which brings us to a point of contention between libertarians and social conservatives. “What sort of licentious den of iniquity would a libertarian society look like,” social conservatives ask, “without laws to uphold standards of decency and public morality”. And if their solution is an abysmal one, their concerns aren’t necessarily unreasonable. I think it is fair to say that, at least in some ways, we’ve become a coarser, less responsible (if more “genuine”, whatever the hell that means) society over the last few generations.

I think the point they miss is not that politics is downstream from culture, but the fact that politics is a tributary into culture. A libertarian society would create a particular form of culture. And in many regards, that culture would be remarkably conservative in its values, habits and behaviors. In many regards, libertopia would look much more like Mayberry than like Mad Max.

This notion might seem counter-intuitive at first glance. How can a society that provides less, or even no, enforcement of traditional values have more popular adherence to traditional values? Because traditional values, for the most part, work. Not universally. Not perfectly flawlessly. And developments might make them less useful over time. But, as a general rule, adhering to them makes for a better life. You’re more likely to be successful, happy, and fulfilled if you work hard, don’t philander, stay in school, exercise sobriety or at least moderation, and have an active spiritual life.

And, in a libertarian society, you’re much more responsible for ensuring your own success than you are under the status quo. Absent the mandated, state-sponsored, safety net, the consequences of vice are more likely to fall on those engaged in that vice. Not only does that affect incentives, that change in incentives can change the culture. If a behavior makes you less successful, that behavior becomes less popular and that change in popularity itself makes that behavior less acceptable.

The cost of vice, though, regularly indulged in, isn’t trivial. You don’t have a lot of prospects in the world if you regularly show up to work hung over or coming down from a cocaine bender. Single motherhood, absent outside help, is a major life challenge to the single mother as much as the child. And being a “player” is a bad reputation because it’s more likely to leave his female romantic prospects in that situation. A liar or a cheat is something that you don’t want to be because your audience has significant incentive not to trust you. In a libertarian society, simple reality provides strong incentives to avoid vice.

But those incentives are not in play under the status quo. The safety net provides a floor on the consequences of vice. You don’t have to believe the cliché of the welfare mother pumping out babies to increase her welfare check to understand that that check does reduce her downside to having sex with a guy who isn’t going to support her. And, on the margins, that matters. You don’t have to be a teetotaler panicking about the dangers of demon rum to recognize that some people will indulge in the nightlife more aggressively if getting fired means they’ve lost their only source of income.

Now, living with the consequences of your vices might seem a brutal, even vicious means of punishment. Harsher, perhaps, than the legal penalties imposed by the social conservatives. However, the removal of the state-sponsored safety net doesn’t mean the abandonment of any safety net. It’s not the case that, before 1932, every minor transgression in human behavior meant certain ruin. People relied on civil society for their safety net. They turned to their churches, the local lodge of their fraternal organizations, their unions and private charities for help when they’d fallen on hard times.

But, unlike the government, these institutions had an ability to draw distinctions, to discriminate. They could demand the person asking for their help change his behavior and refuse him assistance if he didn’t change. But, the government can’t do that. And I’m not sure I’d want it to be able to. Not only is there a real matter of equal protection to consider, but the concentrated political demands of those demanding assistance despite their vices provide a much more powerful constituency than the diffuse expectations of those expected to pay for it.

Unfortunately, the space of civil society has fallen dramatically. In his 1995 essay Bowling Alone, Robert Putnam discussed the decline in American “social capital” and civil society in the post-World War II era. One of the examples he cites is the decline in bowling league participation even as the number of bowlers has increased (hence the title of his essay). However, this was not always the case. Consider this quote from Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America,

“In the United States, as soon as several inhabitants have taken an opinion or an idea they wish to promote in society, they seek each other out and unite together once they have made contact. From that moment, they are no longer isolated but have become a power seen from afar whose activities serve as an example and whose words are heeded”

The America that de Tocqueville was describing was the America of the 1830’s. It was an America where the government played, at most, a negligible role in the life of the country of the life of most citizens. And what he found astonished him. This was in contrast to his experience in the more heavily ruled and governed Europe, where such institutions were much sparser. Huge swaths of the American civil society that remain with us to this day were formed in this era preceding the rise of the government leviathan, the SPCA, the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, various local hospitals, various colleges.

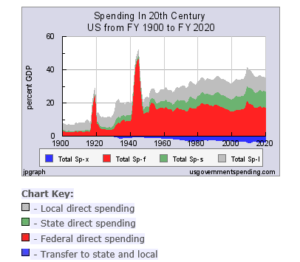

Putnam examines and largely dismisses the notion that this phenomenon might be a result of women entering the workforce. Instead, he suggests, the more likely cause is the rise of television. What he misses is the explosion in the size and scope of government at all levels:

Government grows at the expense of civil society. There’s a crowding out effect. And that reduced role for civil society translates to a diminished respect for traditional values. It’s not shocking, to me at least, that the Baby Boom generation, the first to grow up with this expanded role of government as normal, was the first that turned away from both civil society and traditional values.

“But,” a hypothetical social conservative might counter, “even if limited government will give us much the same thing, surely the right top men could institute policies that would get us there faster.” But, that’s doubtful. As I note before, vice will inevitably have a greater constituency than its absence. Vice, after all, is fun, at least while you’re doing it. And trying to tamp out others’ fun makes you, well, kind of a killjoy. So, when you leave these decisions to the government, there’s going to be an inevitable drift toward vice. That is unless there is an ongoing expenditure of energy on new moral crusades, which people tire of eventually, anyway, the inevitable trend is toward vice.

So, in a world where politics is downstream from culture and where culture is downstream from politics, the sensible stand for social conservatives is actually libertarianism. While it may not give them their ideal world, it is a world far closer to it than they can hope to achieve through ever-expanding government.

Great article! I tend to agree almost entirely. The funny thing is that most Social Conservatives are authoritarians first, Social Conservatives second. Point out all the inconsistencies in their outlook and the slew of unintended consequences from the enactment of their preferred policies and they go from 0 to NPC in an instant. I’d be really interested to read commentary on Romans 13 from one of our Bible-totin’ Glibs.

Yes, finding non-authoritarians on either the left or the right is now close to impossible.

In the old days the left used to at least pretend.

The really telling thing for me with SoCons is cops. My Tea-Party-“the-government-is-coming-to-get me father” goes straight NPC if you dare to breath a word of criticism about a hero-in-blue.

Does NPC stand for something other than “Non Player Character”?

Yes. In his case “a few bad apples,” “most cops are good guys who would fight against a government crackdown,” “Waco was the Feds, local cops would never do that”, etc…..

It took me years to figure out what SJW stood for, the best I could come up with was “Single Jewish Wombat”.

I am asking what the acronym is.

Sorry, didn’t read what you wrote carefully; NPC does indeed stand for ‘Non-Player Character’ (as in ‘scripted, non-sequitur response to an argument)

Hell, I was like that for a while. So was my dad, but to his credit he’s been willing to consider the points I’ve made to him about police abuse, and has come around to my point of view at least somewhat.

#metoo

In the old days the left used to at least pretend.

So did the Right. Ever read “Conscience of a Conservative”? The ideas therein espoused by Goldwater and his ghostwriter Brent Bozell would be called libertarian these days.

And the last honest non-authoritarian leftist was probably Nat Hentoff, and of course he was read out of the movement.

For about 25 years now I have wanted to write an essay entitled “On Being Caesar”.

It is sort of a counterpoint to Romans 13. In that while keeping Romans 13 and Matthew 22:21 in mind, the question is how should Caesar treat his subjects? The point being, when you a have a government “of the people” we are also Caesar.

I think Philemon has to be taken into account also.

So what you’re saying is we’re all Little Caesar’s?

Sounds libellous to me.

Pizza unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s. Pizza unto God that which is God’s.

or, for short: Pizza Pizza!

He who saves his deep dish shall loose his pizza, but he was losses his deep dish, for my sake, shall have everlasting pizza.

I’ve read commentary that states that the government of the day was Herrod and Caesar; both of whom persecuted the church. If you read Roman’s 13 and insert “Herrod and Caesar” for “authority” the narrative that we must be abjectly subject to the state per biblical mandate quickly falls apart

Paul submitted to Caesar to the point of spending years in a Roman jail.

And Peter escaped imprisonment. Could you elaborate on the point you are making?

I am not sure what my point was exactly.

I find Romans 13 incompatible with the American Revolution…until July 4th, 1776, then it was entirely compatible, as the new American government qualifies.

IDK if you’ve ever been read the Christian Libertarian (linked below) but there is some interesting reading there……

I don’t know enough to try to argue exegesis but I find the mainstream interpretation of Romans 13 inadequate by virtue of comparison with the rest of the Bible. There are more than a few times that the (((Israelites))) and later the Christians in Acts went against the state with God’s blessing. And if you are of a Protestant bent, the reformation also was sparked by an act of rebellion so…..

The line between reform and rebellion is a thin one.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TrKqBlZdOTk

see Rutherford, Witherspoon, and the doctrine of the Lesser Magistrate also

https://libertarianchristians.com/2018/06/16/romans-13-for-dummies/

Lot of reading on Romans 13 here.

Yep, the article I alluded to above is listed there:

https://libertarianchristians.com/2008/11/28/new-testament-theology-2/

Romans 13 reminds me of the letter the Khan(I think it was Kublai) sent to the Pope replying to accusations of how horrible the mongols were.

How can we be against God? If we were, surely your God would smite us instead of allowing us to do these things.

That’s paraphrased, but it seems to go with the “Your ruler is always right” otherwise God would not let him be your leader.

I’d be really interested to read commentary on Romans 13 from one of our Bible-totin’ Glibs.

1) submission to authority is a personal discipline as much as it is a social act. Even submission to tyrants.

2) it’s really presumptuous to assume that “authority that oversteps its bounds according to my principles” it the same as “authority acting outside of the power provisioned by God”

3) when an authority is in direct conflict with God, I choose to submit to God.

Aquinas wrote it better, especially around 1028: Linky

My question is, if Natural Rights are set in place by God (as discussed/written about here previously) does that mean that a state that infringes upon or seeks to violate those rights is in conflict with God?

Two responses to that question:

1) probably, yes. There are many biblical admonitions against being tyrants. Aquinas addresses a few of them at the end of his commentary.

2) I think it’s an open question of how subjects are allowed to biblically respond to tyranny. As noted by Aquinas, there are plenty of martyrs who went against the State and were venerated/rewarded, so there is a line in the sand, even if it’s not clearly marked. IMO, that’s where special revelation comes into play.

One good shorthand way to look at it (not perfect overlap, but still) is that Natural Law is a restatement of the second table of the Law.

The key part is “that which is Caesar’s”, which means there are limits to what Caesar can rightfully claim.

Not only are there limits to what Caesar can claim, but there are limits to how Caesar can use the revenues.

Another very short one: One big point is that authority and power are 2 different things. Sometimes they overlap. Sometimes they don’t. God is the “author” in the root of that word, and something that a state does that is contrary to his law is usurpation and tyranny.

You know who else argued that a deity’s law trumps man-made law?

Osama Bin Laden?

Trump?

John Locke?

Thomas Jefferson?

Excellent article!

How can a society that provides less, or even no, enforcement of traditional values have more popular adherence to traditional values?

Depends a lot on which traditional values. There is plenty of those.

8 am not convinced people were more responsible in the past.

“How can a society that provides less, or even no, enforcement of traditional values have more popular adherence to traditional values?”

As he point out, because they work. If property rights protections are strong then achieving success is a strong incentive. IOW, if you get to enjoy the benefits of your own success you will strive for success and thus adopt values that allow you to achieve that end. I am going to say that those conditions would foster adherence to those values much more successfully than attempting to get people to adopt them by force.

You get more of what you reward, less of what you punish.

Well the question i posed was which traditional values. I detailed in a later comment. There is a lot more to traditional values than property and work. Most socons focus on abortion and the gay

Most socons focus on abortion and the gay

And that’s a fair point. My underlying assumption is that the resulting culture would be less inclined toward the carousing that characterize either, at least in the popular imagination. I’m not exactly sure what the equilibrium situation is where gays, for example, aren’t “fabulous”, but boring guys who have to go to bed by 10PM because they’ve got work in the morning and get in a snit about “those damned kids and their bikes going on my lawn”.

I suspect that attitude is more based on age and the amount of lawn you’re protecting, and less on whom you’re screwing.

Politics shape culture but more as a feedback mechanism i would say. There needs to be a culture in favor of welfare before politics puts it in.

A progressive movement in the late 1800s occurred here but didn’t gain too much traction. The Great Depression kicked it into reality. People were ready for welfare. “A chicken in every pot.”

Importing a lot of socialists helped, too.

Meh. America had just as many socialists at the beginning of the 20th century as Europe did, we just had a constitution that limited their ability to enact that agenda. The first part of, indeed the entire, century was a time of tremendous change, war, uncertainty, etc., and socialism was brand new shiny, without the baggage of mass poverty and murder it would later accrue. I grant those people the benifit of the didnt-know-better doubt. People who continue to espouse that philosophy after it’s massive failure are different, and should be publicly exposed, shamed, and ridiculed.

Politics provides part of the reward/punishment that determines whether a given trait or practice is successful.

Many cultures support relatives cadging off of someone’s success, so the leeches dragging down hard work etc. aren’t exclusively government leeches. My great grandfather hit the road and left his village to get away from family leeches, starting the cycle that led my branch of the family to much greater success.

I’m trying to imagine something like the Moynihan Report being published by FedGov today.

The title alone would get him exiled.

in a world where politics is downstream from culture and where culture is downstream from politics, the sensible stand for social conservatives is actually libertarianism – as you observed they are authoritarians so no. And libertarianism does nothing against pornography abortion the gay sex work drugs violent video games and that damn music the kids listent to, hell it would enhance all those. Social conservatives have a lot more going beyond hard work and single motherhood

And libertarianism does nothing against pornography abortion the gay sex work drugs violent video games and that damn music the kids listent to,

Thanks for the feedback. But, I disagree, at least in part. If you spend your life doing drugs, jerking off to porn, drinking, going home with random strangers every night, etc., without any subsidy for your behavior, you’re going to have a pretty terrible life. Those behaviors aren’t fundamentally sustainable. So, without the subsidy (i.e. government policy), people who practice those behaviors on a continued basis, will fail. That has cultural ramifications. People don’t want to imitate the people who have crappy lives.

“Those behaviors aren’t fundamentally sustainable”

Twice a day whether I need it or not. Thrice on Sundays. Jerking off hasn’t destroyed my life.

*pushes coke bottle glasses up nose and applies Nair hair remover to palms*

The us was more libertarian in the 19th century than europe and there was plenty drinkin and whorin to go around

Not to mention heroin.

Sweet, sweet heroin…

Raises finger to counterpoint on the impact porn can have on a relationship/sex life……..thinks better of it……Homer Simpsons back into the bush

*thinks about pointing out the moral conclusion arrived at by some that porn is low key adultery, but decides to join Bob in the bush instead*

Really? Huh…

No children or STDs possible, never even meet the other person, let alone develope an emotional attachment, and zero risk of a bastard… yeah those people need to reflect on the parable of Plato’s cave (sounds dirty, Plato’s cave, donit?)

If you spend your life doing drugs, jerking off to porn, drinking, going home with random strangers every night, etc., without any subsidy for your behavior, you’re going to have a pretty terrible life. Those behaviors aren’t fundamentally sustainable. – i am unconvinced and see not much evidence of this.

I’m kind of with Pie on this one. There’s a difference between doing things you enjoy, and letting them control you. Look towards all of the Sullum articles about the people who do drugs responsibly.

There’s a difference between doing things you enjoy, and letting them control you.

I don’t think that line is as bright as you do. Take, for example, consumerism. The single biggest thing that reduced my urge to buy crap was to cut the cable. I wasn’t a shopaholic, but it was amazing how different my mindset became when I wasn’t being inundated with hours of advertising every day.

Similar changes happened when I stopped consuming porn and when I started drinking less frequently. None of those things controlled my life, but they each impacted me in ways I didn’t expect.

I don’t think there is a bright line, and I think the line is different for each individual. That’s one of the reasons I tend towards libertarianism. I don’t want to decide for others where that line should be, nor do I want people to make that decision for me.

I agree on the Libertarian part, but I think that the subsidy aspect is spot on. There are many behaviors and lifestyles that are subsidized by government intervention. Some are “traditional”, and others are not. However, it’s hard to get a good read on the viability of non-traditional behaviors because of the subsidies. History at least shows that the traditional ones are viable sans subsidy.

%h

“…exercise sobriety or at least moderation…”

Aaaaaand I think you just lost this crowd.

I favor moderation in a moderate amount of things.

Moderation in all things is too extreme for me.

-Robert A. Heinlein

Even Westvleteren monks?

Beer enables me to spell some weird words.

Depends, if I could consistently get their beer at the $3-4 a bottle range (IIRC, that’s about the price to go at the monastery) I’d definitely be drinking it more.

Moderation for me but you are on your own. Moderation may mean different things to different people.

“I drink moderately”

“How much? A couple drinks a day?”

“Oh, maybe a little more”

“Like a pint of bourbon a day?”

“A little more than that”

“Would you say a day a fifth then?”

Hell, I spill that much”

To me this just means no drinking at work (usually).

My first real job out of college had a tradition of meeting in the shop and having a beer at 5 pm on Friday’s.

I worked several weeks in southern China for a different job. The beverage choices at lunch were tap water or beer (peejoo). I didn’t trust the tap water.

I met a Belgian guy there. He was an interesting character. He regularly got rip-snorting drunk at lunch, took an hour siesta afterwards, then was back on the job like nothing ever happened. He also had a Belgian wife and a Chinese wife who didn’t know about each other.

Dayum… now that is how you shitlord.

Right off the bat, misses a golden opportunity for a “to be sure”.

*goes back to reading*

Great article! I loved this line:

In many regards, libertopia would look much more like Mayberry than like Mad Max.

I agree with this. While McAffee is fun to watch, I don’t think most of us would have the desire, energy or livers to live like that.

I know the Little House books were partially fictionalized but yes, I imagine society would skew a lot closer to that than anarchy (as much as I love the Wasteland).

McAfee is a great character, but if everyone were a McAfee, I don’t think that would be an ideal outcome.

He’s example 56,549 of “the rich and famous can get away with it, but you can’t”

Not everyone would be. It is not everyone’s nature. Also I don’t like getting fucked up on consecutive days and cannot understand how people are capable of doing that. If I get drunk today I don’t want to do it again for at least 3 days if not more. There is a certain pleasure in having a hangover most of the day, not drinking much, and then the next day waking up fresh and feeling good.

Me, I like to have a few drinks and unwind, but I don’t get drunk. I don’t think I’ve been truly drunk in about thirteen years now – the last time I got ragingly drunk was March 17, 2006, my last day on active duty. I don’t like being unable to control my emotions. I had always tended to be an angry drunk, and I knew it, so after almost getting in a bunch of fights that night and getting kicked out of the bar (to my wife’s utter embarrassment) I finally asked myself “Why do I do this?”

I don’t like being unable to control my emotions. – I sometimes feel getting drunk alone – which i try not do do but sometimes fail – can be therapeutic for me for this reason. I go through a lot of emotions

Yeah, when I’m sitting at home watching a football game is probably when I end up drinking the most. Nothing to set me off at home.

Also, I’m much fatter these days and thus have a higher tolerance than I used to.

Yep. As I’m aging, I’m going from a placid drunk to someone who gets “triggered” about stuff more easily (though I don’t think it’s just age, but the circumstances in which I find myself that are less than ideal for me at the moment). I’ve always prided myself on having good control of my emotions, but that’s been something I’ve needed to work on more in the last few years.

No more drunks for me. I’m not liking the results very much.

Excellent article – I don’t have much to add other than I’m looking forward to the discussion.

Slightly on-topic:

OFFS. Is there no limit to the damage libertarians are doing to this republic?!

ugh link

You know who else damaged a republic…

Sulla?

Chancellor Palpatine?

FDR?

Abe Lincoln?

The F-105 Thunderchief?

The Triumvirate?

Pretty much every US President since Monroe?

Hey, save a good word for Silent Cal.

The Gap?

Ah yes, Chris Hughes, who became a billionaire because he had the good fortune to be Zuckerberg’s roommate.

I nth the excellent article comment. The problem, of course, comes in with the whole “responsibility to proselytize” and accompanies many SoCons, in the same it does with progs. By no means is that always the case. A generally “bourgeois” society run by traditional (voluntary) norms, but one in which the consequences you face for engaging in crack filled orgies every weekend are personal and social, not legal, is pretty close to my ideal.

SoCons and progs are branches of the same progressive root. Nothing makes sense until that connection is made.

i agree to that except I would outlaw cleavage to keep decorum

You’re off the island.

*Covers up plunging, hairy neckline*

Do you want civil war?

Cause that’s how you get civil war!

Great reading! Now to try to convince all the others to live that life style. Some of us live on the taxpayer teat, we too are the victims of public ed, high taxes (in days gone by and even now) and the vote buying of politicians. Mea culpa…

Huge swaths of the American civil society that remain with us to this day were formed in this era preceding the rise of the government leviathan, the SPCA, the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, various local hospitals, various colleges.

Yea but these things are all too important to be handled by the private sector. Observation of history suggests that centralized control and government bureaucracy are the most efficient and providing goods and services to people. ///thingsthathaveliterallybeensaidtomyfacebyprogs

To some up my comments, I honestly think libertopia would have somewhat more personal responsibility for some, less welfare dependency and more work, but also lots of destitute due to bad habits. But they would reproduce less and maybe the gene pool would improve… People make really bad decisions. Some people are just using up oxygen for no apparent reason – the romanian phrase is along the lines they do nothing but shade the ground. Some are lazy or worthless or prone to addiction on any sort. In the past society was more religious and with little safety net and plenty of this happened. this is what motivated the growth of statism: people make bad decisions and top men needs tell em what to do.

But I do not think it would lead to anything socially conservative in the US sense of the term. I believe sex work of all sorts would thrive and nothing would stop abortion. There wuld be plenty of drink and drugs – and sufficient number of people still functional, hard work and hard drink/drugs. Not all but at least some. ANd while stuff like single motherhood would be discouraged, it would be different that the stigma religions attached to out of wedlock sex.

But perhaps the everpresent prospect of destitution could instill better habits and decisions, at least at the margins. I tend to believe that subsidizing bad habits and decisions doesn’t reduce them.

I said as much and consider the welfare state to make a lot people not work for example. But for some. Not all. History is somewhat of an indicator, though not fully relevant because in history without a safety net, there were still things discouraging good habits, like rigid class hierarchies, feudalism, etc. Also capitalism and economic growth changes a lot. The economy and tech now are not what they were in the 1800. So history is not fully relevant. But it is an indicator.

I honestly cannot fully tell what form a libertarian society would take given the current level of tech and economy. But it cant be worse than what we got

As i mentioned elsewhere in the thread, we don’t really know how wide-ranging the consequences of killing government subsidy (both financial and ideological) would be on modern behaviors. Maybe there would be a drive-thru abortion clinic on every corner. Maybe abortion will be as popular as neo-nazism. Maybe being a drunk will be ubiquitous. Maybe it’ll be impossible to hold down a job as a drunk when companies aren’t restrained by ERISA and the plethora of other employment regulations.

Whoa, nelly!

Beet sugar and dates don’t sound like a good start for beer, but I’ll try anything once.

Yeah, I’d sample it.

About a third of all segular sugar on the market comes from beets rather than cane. I’m not sure if they’re talking the molassas equivalent or the stuff that’s chemically indistinguishable from processed cane sugar.

Based on most of these, just the stuff that’s close to cane sugar. Both beet sugar and dates are common in some Belgian Dark Strong beers. The bourbon barrel aging would be an American twist on it. I’d be more curious what yeast they used to ferment it out.

This kind of stuff is why a lot of craft beers make me roll my eyes. So much of it is about making weird beers for the sake of being weird. Who the hell is dying to have a beet and date flavored beer?

Make me a good lager or bock that tastes like beer and I’m happy.

As Neph mentioned above, that is a common flavoring, especially the beet sugar. Belgian sugars are all beet sugars, I think.

The date thing doesn’t need to be added directly, you can get that flavor from dark sugars and the right yeasts.

But blech on the bourbon barrel part.

In a couple of the brewing books, they mention that the Belgians used beet sugar because it was the cheapest available to them. Not for any flavoring purposes (since it’s all fermentable anyways).

See that beer in my avatar. It was made with beet sugar.

http://www.candisyrup.com/

They shouldnt be the start of the beer. The malt should be the start. The sugar makes it easier to bump up the ABV level, adding ferementable sugars without unfermentable ones. Keeps it from being sickly sweet. Since it is beet sugar and an imperial stout, I would bet on a dark candy sugar, which could give some really interesting flavors. Same for the dates, adds some flavors and some more fermentable sugar.

Nicely done.

Kind of fits the topic. Private business rewards customer for being responsible.

https://www.foxnews.com/food-drink/canada-bar-patron-ticket-drinking-responsibly

That’s a cool idea, good on them for doing it.

However, I’m not sure if it’s wise to tell the guy to come on in the next morning to tie one on….before driving his car home lol

Excellent article, really well written and interesting.

*rimshot*

There is more than one formula that leads to Libertopia. Jeffersonian agrarianism in the suburbs is one; pirate utopia is yet another. The rest is merely aesthetic preference.

pirate utopia is yet another

Can we teach the natives to play lacrosse?

Of course.

I thought they preferred basketball.

Those aren’t pirates

But cheap rum is not my drink of choice

That is a difference between you and me.

You can do better than that.

Better Beauties

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2019/05/09/climate-change-is-helping-older-trees-grow-better/

Climate change is a conspiracy for Cypress trees. And who would want Cypress trees back in Lebanon????

S/Cedar/Cypress/g

Switch those.

: Quits for the day:

Kings of Isreal?

Suffering the consequences of one’s ‘immoral’ behavior may well cause some reduction of those behaviors but there is one mitigating factor in a stateless society which might make those reductions smaller than one may think. Just getting by would be much cheaper, and not just because the man is no longer picking your pocket, but the removal of regulations would open up lifestyles not currently possible (or at least not plausible) A junkie could very well get by only doing the random odd job here and there, while still being a junkie. If food and shelter could be had cheaply at old fashioned Flop and Slop houses, where conditions may not meet today’s government enforced standards, living a life of depravity might not be the disincentive that we assume it would.

If food and shelter could be had cheaply at old fashioned Flop and Slop houses, where conditions may not meet today’s government enforced standards, living a life of depravity might not be the disincentive that we assume it would.

In and of itself, you’re almost certainly right. But, again that’s where culture comes in. There’s no way you’re anything other than low status if you’re sleeping at the local Flop and Slop. Now, that might not be a deterrent to you, personally. But, it would almost certainly be a deterrent to someone considering taking up your lifestyle. And if you get that multiplied over enough iterations, it becomes a cultural expectation. People don’t go that route because it’s not the thing to do.

Thanks for all the positive feedback, and skeptical feedback, as well, everyone.

Folks brought up some really interesting points that will certainly help to hone my own thinking on the topic. Like anyone’s thinking on anything, my thoughts are (or at least should be) only a draft.

I’d suggest my biggest mistake here is using the term “socially conservative”, with its attendant political implications, rather than, say, traditionalist. What got me writing this article was something someone linked here where a woman tried to argue that libertarians were parasitic because libertarianism could only exist within the context of a socially conservative society. And, to me at least, that gets it exactly backwards, or at least misses a key element. Libertarianism reinforces the traditional values that make libertarianism sustainable. It’s government intervention that undermines those values. And when the interventionists, including the authoritarian traditionalists, get the government involved to support, even what they believe to be good values, it only serves to undermine those values.

Monsoon!!!!!! Incoming!!!! Monsoon season has begun in the Balmer, hon!

Yep. And half of the computer systems for the Bmore government have been hacked and are currently down. Word is they’re being asked for ransom money. My friend suggested maybe they could just sell some more Health Holly books to pay it off lmao

Just read about that, what a cluster fuck.

I’m sure it was a failure of the private sector, somehow.

I like how their response is just to shut down all the servers and work only by phone. Although I’m sure they’re probably working just as effectively as they were before. i.e. not at all

The Cleveland Airport got hit with ransomware a couple weeks back. Sounds like some more people figured out the government makes better targets then individuals.

This is apparently the second time in a year for Bmore too. I guess unfortunately the mayor was too busy being a corrupt charlatan to fix the problem after the last hack

I was just stomping about in a Hessian cemetery in Texas that’s in the middle of a near libertopia. Driving around a section, the land facing the river is weekend homes with new cars parked in pretty lots; further away, trailer houses with dogs loose in the street. Libertopia reminds me of a crack I made years ago while advising a Land Use Control Board regarding the unicorporated county: the great thing about the county is no building codes; the bad thing about the county: no building codes.

I’m not going to miss this chance to join those who, while responsible and productive in their own homes and businesses, are nevertheless wary of socons. I’m as conservative as anyone here, but I generally hate conservative movements and all the noble church ladies, their committees and appeals to the legislature. I think libertopia will always be that way, like the county without codes; but the problem is that team libertarian only keeps its fences up so long as the goats stay in and the coyotes stay out and not many nails better than that; we don’t care whether you tend your fence; we do care if your goats come stomp our car. But the socons won’t stay on their ranch, married for life, abstaining from abortions, and all their good goop; no, they’ll be at our gate pissing about whether we’ve mown our lawn recently, all chanting in their Sunday best except the one guy who rode to the capital to advise the governor of the libertarian evil, iniquity, and debauchery back in Freedom Parish.

Oh, don’t get me wrong. I have no more use for the meddling church ladies, whether on the right or the left, than most here. My observation is that Freedom Parish really wouldn’t have all that much evil, iniquity, and debauchery. Their butting their noses in to make sure you toe their particular lion sows the seeds of the social authoritarians’ own undermining. The very government they call in to make sure their kids learn good, Christian, values inevitably eventually decides to mandate “xhe” and “xher”. It would be better, from their own perspective, to limit the power of the government and evangelize their values through voluntary cooperation.

Sorry about the tone; I get defensive.

Libertopia reminds me of the invisible hand and the rational investor: there will be a tone of ugly bits on the fringes even on a good day. I think that’s one of the virtues of this site’s membership: most folks tolerate mistakes, problems, friction, residues when a greater philosophy can deliver a greater good, whereas the meddling, progressive types can’t stand any skinned knees and must regulate and enforce knee pads for everyone until we’re wearing them to bed and paying four prices for the required UL, NATO, and DOT certification stickers. One wonders which arguably neato stuff like interstates would survive and how many Notre Dames would be sold off by the brick during a bad quarter for relic sales. Would there be dogs in every street? Just nice dogs? Would I melt down my barrel blowing away dogs in the street?