Image source: Wikipedia Image

Once again let’s summarize the premise:

Cocoa Hoto enters the cafe Rabbit House, assuming there are rabbits to be cuddled. What Cocoa actually finds is her high school boarding house, staffed by the owner’s daughter, Chino Kafū, a small, precocious, and somewhat shy girl with an angora rabbit on her head. She quickly befriends Chino with the full intention of becoming like her older sister, much to Chino’s annoyance. From there she will experience her new life and befriend many others, including the military-influenced, yet feminine Rize Tedeza, the playful Chiya Ujimatsu who goes at her own pace, and the impoverished Syaro Kirima who commands an air of nobility and admiration despite her background. Slowly, through slices of life, often comedic, Cocoa becomes irreplaceable in her new friends’ lives, with Chino at the forefront.

Source: Wikipedia

This anime isn’t as awful as the summary makes it appear. It’s a standard slice of life comedy with around six or so characters who simply make small talk and do funny and cute things. It is by no means high art, but a fun way to spend 20 minutes an episode if you like anime. Nothing to recommend for a non-anime person to watch, however.

Japanese: ご注文はうさぎですか?

Romanized: Gochuumon wa Usagi Desu ka?

English Title: Is the Order a Rabbit?

ご – go – this is an honorific. This is essentially untranslatable in English, but if you have to get point across you can use “honorable”. The reason it’s used here is that when you are asked for your food order at a restaurant, even in the most casual of places, the staff will almost always use “go” in front of the word for your order which is…

注文 – chuumon – order or request.

は – ha – (pronounce “wa”) – grammar particle used to denote the topic of the sentence.

うさぎ – usagi – rabbit. Normally animal names are written in katakana – ウサギ – and I’m not sure why the hiragana is used here. The word rabbit is quite common so that may be part of the reason. Female names are also frequently written in hiragana as as it it tends to be viewed as “cuter” so that could also be part of the reasoning here. The story is about a cafe full of cute girls.

です – copula. More below on this. In this particular case it is translated as “is”.

か?- ka – another grammar particle that changes a declarative statement into a question. Technically the question mark, borrowed from the west, is unnecessary, but frequently used.

A literal translation would be “as for your (honorable) order, it’s a rabbit?” The actual English title is very close to the Japanese.

When I first started learning Japanese I had little interest in linguistics. However, I’ve always had an interest in English grammar. So I had no idea in English the verb “to be” served dual purposes. It can be used as a copula and for the purpose of existence.

In linguistics, a copula (plural: copulas or copulae; abbreviated cop) is a word that links the subject of a sentence to a subject complement, such as the word is in the sentence “The sky is blue.” The word copula derives from the Latin noun for a “link” or “tie” that connects two different things. – Wikipedia

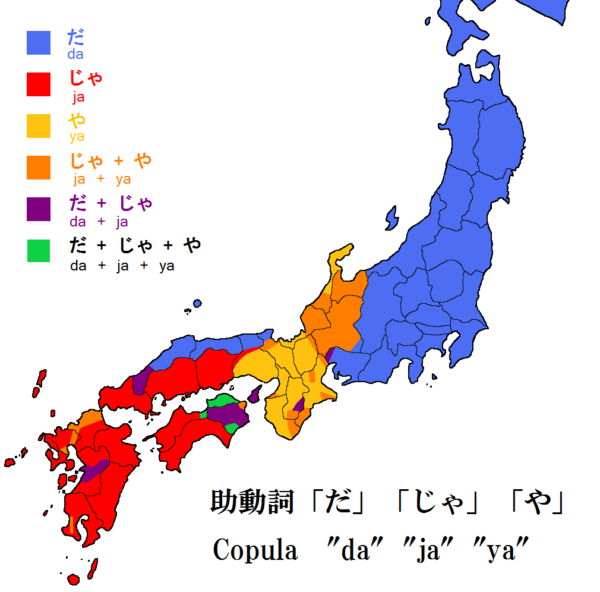

In Japanese the somewhat well known “desu” or です is used as a copula. Note that “desu” is polite. There is a plain form that is also very commonly used “da” or だ. A big thing note here – the plain form copula also varies depending on dialect and region.

Source: Wikipedia

To provide an example let’s look at the following:

この部屋は台所です。Kono heya wa daidokoro desu.

“As for this room it is the/a kitchen.” More naturally – “This room is the kitchen”.

Japanese doesn’t have articles (“a” or “the”) like English. My Japanese friends learning English find figuring out which article to use in English maddening.

However, unlike English, Japanese has two other words that are used for existence – “aru” or ある and “iru” or いる. In the polite form they are “arimasu” or あります and “imasu” or います. Why are there two forms? Because it’s Japanese and things need to be difficult. Animate objects take “iru” and inanimate objects use “aru”.

台所に猫がいます。Daidokoro ni neko ga imasu.

“There is a cat in the kitchen.” OR “The cat is in the kitchen.” Without context we don’t know if we are talking about our family pet or if the neighbor’s cat climbed through the window. Welcome to the obscurity of Japanese. A cat is animate so we use “imasu”. Note that the particles we are using here are different compared to the sentence with “desu”. We are using the particles “ni” and “ga” and not “wa”.

台所に冷蔵庫があります。Daidokoro ni reizouko ga arimasu.

“The refrigerator is in the kitchen.” Last time I checked a refrigerator isn’t able to move on its own volition so we use “arimasu”. A car also doesn’t move of its own volition so we use “aru” when describing the existence of a car. However, a robot despite being a machine does move by its own volition so robots use “iru”. Simple, right?

There you have it. In English the verb “to be” accomplishes what takes three different words in Japanese – desu, arimasu and imasu. In their plain forms these are iru, aru and da in standard Japanese.

Actually, thinking about it further, if we use very polite forms of Japanese we need some additional forms for existence and the copula. I’ll save that maddening topic that is polite Japanese for our more fluent in Japanese Glibs…

Hi, Lurker is lurking………

Burn the witch, burn her!

I need to learn too many other things,. Japanese won’t help too much in my endevours,

so I’ll Lurk and learn by reading Ya’llins,

I don’t know Japanese, either. And for the same reasons as you.

But I will always punk your diorama-making self, buddy.

We are the only three glibs. Everyone else is a weeb.

Note to Swiss, SP, Suthenboy, OMWC, Mexican, etc.: Count Potato called y’all “weeb[s.]”

You’re trying too hard, flow Dude Flow….

Thanks for the advice.

OK, not Suthenboy.

that was for DNT, I agree with you, they be Weebs and shit

I liked your comment on my water, it’s now in my bag of tricks, thanks!

Thanks! I’ll try to post some actual photos of whitewater, and draw in the arrows. Unfortunately, drought season here in VA. Waiting for remnants of tropical storm to roll through and swell the rivers with rain.

So you think “Random Internet Guy” is not a “Guy” but a “her?”

HAHAHAHAHAAAAAA!!!!!!

I think the implication is that RIG is Yusef.

A Glib asked for in home HVAC Service, and Her Husband said ” No Random Internet Guy” is coming to their house, I thought it funny, I am well known and don’t hide my true identity,

so RIG

What do you think of the Carrier Comfort Series?

Carrier is overpriced and over controlled for no extra benefit, same for Trane.

Goodman, ICP and Rheem are my first choices, simple and tough.

Super High efficiency only works with a tight, sealed and insulated house, even then the ROI isn’t worth it. Buy cheap, and CHANGE YOUR FILTERS!!!!

I have Rheem and it’s failed more times than I can count. Then again I had a ton of problems with my Tacoma too. Have I mentioned I’m not lucky?

@FM, it always depends on Who installed it, Salt spray doesn’t help either

Probably gators climbing on the box looking for something to ream.

I thought of the three Carrier series, the Comfort weren’t super efficient.

So Goodman, Rheem, and Insane Clown Posse?

Also, the size of my place is 1630, right between 2.5 and 3 ton. Which should I get?

Carrier is overpriced and over controlled for no extra benefit, same for Trane.

I got an American Standard (same as Trane) for my upstairs AC unit. It’s worked OK so far.

One of the AC contractors I talked to tried pushing this high end unit with all sorts of fancy controllers. I don’t remember now who made the AC unit, it wasn’t American Standard/Trane. Someone else. I didn’t want it. Given I live in New England, I can (and did) justify the Cadillac of Boilers (Buderus), but I couldn’t justify a high end AC unit which just covers the upstairs of my house.

The folks that installed my American Standard were not only the cheapest but came with the best recommendations. Co-workers of mine hired them for other work and loved them.

So, random word of mouth guy?

I got a Coleman. Cheap, works good, but loud as hell.

Unless the comment was Brooksed, it looks as though the “her” in “Burn the witch, burn her!” is Random Internet Guy, regardless of whether or not Random Internet Guy a/k/a RIG is Yusef.

Are you saying that Yusef is a tranny?

Cocoa Hoto enters the cafe Rabbit House, assuming there are rabbits to be cuddled.

This sentence made me think the anime was going to be furry porn….

I first read anime titties and was like finally.

Damnit

I do that every. single. time.

It’s why I keep using it….

#metoo

Gets me every single time.

Just watch, one of these days it will actually say “Anime Titties” and we’ll be like 200 comments in before anyone notices.

? the Anime Titties series. ?

https://twitter.com/Ely_eee/status/1160396250094526464

https://twitter.com/megumi_koneko/status/1177228401519804418

A new use for them

https://youtu.be/GLKhkxB02tQ

I’ve seen sandbag bench rests before but never a funbag bench rest.

Its a great concept. I think we found a good use for those female recruits. I’m going to throw out the idea at the local gun range that they should offer rentals.

Thank you, this was very interesting. Have you already elaborated on how to decipher whether to use polite or plain form? Or is that coming?

I’m fascinated by language forms and structures, and how those do, and don’t, reflect social structures. Reflect and reflected by, it’s bi-directional.

No, not really.

In Japanese you essentially have humble and honorable forms that you can also use in a polite or plain form. But in normal every day life outside a business context you would use polite forms with people you don’t know and a mixture of polite and plain forms with people you do know depending on the relationship.

Initially it’s a bit confusing, but in practice it becomes clear. Since I don’t use Japanese for business I’m weak on honorable and humble forms. But for things like stores, hotels and the like and that kind of honorable form I’m OK.

I just expect everyone to treat me like I’m God.

The customer isn’t a king, but a god in Japanese.

Until they want something that isn’t allowed by the rules, even if it makes sense.

punctuation God? OK, I’ll give you that…

You keep me on my sad little toes,

I’d treat you like your God but there is a problem.

Really…you are, a god:

Thanks. I think it makes sense that “use makes plain.” Eventually at least

I look forward to more of whatever you have rolling along here.

Copula?

As in Francis Ford…

Srsly, I can understand a polite form for copulation (if I’m interpreting this right), but srsly, is there a polite form for existence?

Living? simple and to the point.

Yes- iru becomes irimasu. And aru becomes arimasu.

You can also make it humble – aru = gozaimsu.

Or to really blow your mind iru can be irrasharu or oru. And you can also make them polite irrashaimsu or orimasu.

Sorry make that first sentence “imasu”. On the phone and I usually don’t write in romaji!

You forgot the “T”. It’s “Tiramisu”.

Just finished watching “Saga of Tanya the Evil” it’s finally available on streaming….

I started that one but never finished. What did you think?

I watched the series. The movie just became available.

You have to fully suspend your belief about how the battles are actually fought. It’s utterly unrealistic. If you can get past that the idea of an everyday evil salaryman being reborn as a young girl and being tested by God to believe in him is really an interesting premise.

The character is absolutely evil, but you wind up rooting for him/her. Also the idea of setting in an alternate world where WWI and WWII didn’t happen, but instead were combined in the late 20s is also rather interesting.

Thanks. Maybe I’ll give it another try.

Fucking gingers*:

https://twitchy.com/dougp-3137/2019/09/26/daily-beast-prince-harry-struggling-with-eco-anxiety-so-severe-he-struggles-to-get-out-of-bed-in-the-morning-and-people-have-thoughts/

*my sister is a ginger, she’s a little cray cray too.

He needs to snap the fuck out of it.

I get school children being frightened, but he is a grown man. You’re scared? Go outside and look around. It’s a beautiful world.

He and Meghan are welcome to leave public life and become recluses.

And fly coach…

Imagine how hard it would be if he had to go to work.

I was a ginger. Now my hair is snow white. Does that mean I now have a soul?

Yes.

No, you lost it when your hair turned White,

/just like me……

No it means you need to drink more Orphan blood and get your color back.

My wife is a Ginger, also a little crazy

fortunately mostly in a good way

Pics or it didn’t happen.

I have always been a half-ginger, with equal amounts of blonde.

HOWEVER. Now that the white is starting to make itself known, I look like a funkily-dyed blonde. I asked my brother if I looked my age and he said no, BUT that I needed to dye my hair because it was distinctive and not in a good way. “People stare at it because they can’t figure out WHAT color it is.”

“I have always been a half-ginger, with equal amounts of blonde.”

HAWT

Seconded.

No half Gingers! you are stricken with No Soul Disease! One drop and all that!

May God bless our cursed Souls,

/jif, God Bless you

Oh wait. Gingers are one-drop ruled?!?

So Megan probably needs a real man to take care of her needs then.

I always had the vibe he was a fun-loving cute-as-a-button happy-go-lucky dude’ but damn, now he’s just a random asshole celebrity. Say, Harry. Give up all your money and possessions to the poor and live like normal people, then I’ll be impressed.

He’d probably be happier if he gave up the wife. This all comes from her, I bet.

Could well be.

Inner monologue: “Goddammit. Another day on this fucking earth and my brother’s bitch has another litter putting me even further away from the crown. Another day of plant food and smiling and doing meet and greets. Fuck I want to go to Balmoral and hunt.”

Megan: “You look sad. What is it?”

Inner monologue: “If I say anything other than her pet causes, the cunte will go off again.”

Harry: “Ecoanxiety”

Megan: “Of course! Hurry up so we can eat out rabbit food for breakfast”

Pretty much.

I’ve seen this is action – it ain’t pretty.

The remedy is poker face.

If he doesn’t have a woman who’ll let him poker face then he’d better have a strong poker face when he’s feeling blue – cause that’s gonna be most of the time.

On the hot crazy matrix she is the limit others can only approach.

I’m sure you’re right.

He seriously needs to hang out with his army buddies, eat a steak, drink some scotch, and bang some strange. Maybe throw on an Africorps uniform.

He served in Afghanistan – you’d think he’d have a bit of perspective.

and Afghanistan actually is the rocky hellscape with searing heat alternating with brutal cold that the climatephobics see coming everywhere. Maybe it’s PTSD?

https://youtu.be/4gjT9ujNOm0

Maybe Harry has daddy issues (Daddy is most likely not the Prince of Wales)?

A car also doesn’t move of its own volition so we use “aru” when describing the existence of a car.

Would self driving cars use a different word?

Funny I’ve thought about that. My guess is that because they have historically been non-volitional they’d continue to be referred to that way.

That makes sense.

OT: The Eagles are dirty little shits. Two plays, two helmet-to-helmet hits. And the refs missed an obvious one.

Come on, man. I’ve had a rough night and I hate the eagles.

Everyone hates the Eagles.

Well when you grow up in southern NJ you have no choice.

Naturally most of my office is Giant or Jet fans.

My shooting buddy is a Giants fan. We were out drinking together when they won the Super Bowl. That’s as close as I’ll ever get being a Vikings fan.

Seeing the Vikings fail spectacularly never gets old.

Thanks

I throw the Bullshit Flag. It is known there are no Jets fans in the wild.

They exist. As do Mets fans. I’m surrounded by them. Fortunately they’ve finally been put out of their misery.

If I liked baseball and had to choose a local team, I’d be a Mets fan. The Yankees can fuck right off.

Yeah, the Yankee and Giant shills are terrible. Could you imagine how Odell Beckham would have been treated had he been on the Jets?

I’m not a fan of the NFC

East in general.

Duh, they’re from Philadelphia. Comes with the territory

My brother-in-law is from Philly, and lives in Dallas now.

I’m from the Philly area.

Oh.

Uh…

Right…

I’ll… uh… right…

And multiple facemask violations too.

My handwriting, and I’m talking printing, not cursive, is so bad that I can barely read my own grocery list. I would never be able to write legible Japanese.

Oh, amen. List maker apps on the phone really help.

Good tip.

I just tell Alexa and she puts the list on my phone. Really handy.

and some poor bastard at the NSA has to read your grocery list! Will no one think of the Big Brothers?

They are watching…….

They’ll wonder how 2 people drink so much milk?!?

Hey Alexa

Add to my shopping list

Bath salts

Bread

Meth

Peanut butter

White claw

If I didn’t have to write a check to my landlord every month, I probably wouldn’t hand-write anything ever again.

Same.

But for the most part, I just gave up. I know type everything. Started taking my laptop to more meetings.

If I must take a notepad, I make an effect to type out my notes as soon as I get back to my desk.

Otherwise, I print everything; envelopes, labels, etc.

If I see anyone in my office sending an envelope with a hand written envelope, I shame them into learning how to print it.

err… you know what I meant

*grumbles* edit button….

Dude, picking up a pen to write on an envelope is way more efficient than printing it. Open Word, find template, type in stuff, fetch envelope, go to printer, put it in correctly (and you have to remember which way that is), go back to your desk, click PRINT, go back to the printer and wait for it to come out. It’s not much better if your printer is right there.

Pick up the damn pen, geez.

You forgot the 7 minutes of disassembling the printer to clear the shredded envelope paperjam

I so forgot that part. *headdesk*

Also, toner is out. “Where’s the toner?” “I dunno. Where’s the toner?” 30 minutes looking for a new toner cartridge, which the department admin keeps in her drawer to guard it with her life because it costs like $4,000.

Then putting the printer in the trunk, taking it out to field with a few of your friends and smashing it to bits with a ballbat, while “Layla” plays in the background,

PC Load Letter

My handwriting is terrible and my Japanese is not nearly like it at all. And Japanese’ written Japanese isn’t always great either. Seeing native speakers, er native writers, really opened my eyes that it doesn’t need have to be perfect.

I forgot how much time goes into laying out Grass on a larger Diorama, days and days, very boring, and it must be done in order,

/First World Problems….

Art is suffering.

I must be losing it. I signed up for N5 in December.

I’ve been told that one isn’t too bad!

Gambatte!

ありごとうございますせんぱい!

It’s all easy, right? They print the answer right there or say it in your headphones.

Huh. Here I am, happy I found the proper translation for “tilt” in Hungarian. Folytat, by the way, thanks Mojeaux.

Good work, Sensei.

You’re pinball honky with stars in your eyes?

Glad I could send you down a random rabbit hole!

Now you can folytat at your windmills.

Szélmalomharcot folytat. Or for a native Hungarian idiom, értelmetlen tevékenységet folytat, “beat the air”.

Tres Cool has also been thanking me profusely for introducing him to sksksksks, and I oop.

Do you have a scrunchy?

Plain office rubber band.

I have a 9 year old daughter, I’ve been aware of the vsco girls for a while now. Fortunately, she hates them and mocks them ruthlessly, which I take as a sign I’m doing decent at the whole fatherhood thing.

For my kid, they don’t even register on her radar. Unrelated: she has always had a water bottle fetish, though, so I found the vsco girls when I went looking for a hydroflask after she mentioned it.

I thought that was Crusty.

Is that the noun or verb form?

At least you’ll be able to sleep tonight…

Verb, it translates to continue, to exercise, to practice, to pursue, to take up, to prosecute, and several other related English verbs. Essentially to start something, but with a more aggressive or vigorous connotation than something like elkezd.

I’d be amazed if it was both as it in English. Especially as archaic as the verb is in English.

Exactly what sent me down this rabbit hole to begin with. Modern English tilt, as in incline, would be hajlás for the noun and lejt for the verb. Finding a suitable translation for starting a jousting match was a little harder.

Sometimes I wish my cats could speak in ways that don’t involve puking freshly-eaten food in their beds.

It could be worse. It could be freshly-eaten food in your bed.

Now I feel better

They’re just saving a snack for later.

Like braces.

haha

No kidding. They seem to prefer that to eating from the bowl.

It’s not just your cats.

Fucking cats have such weak guts. They puke more than my prom date did.

Probably should have kept your clothes on.

LOLOLOLOL!!!

Har. Actually never been to a prom. I just assume they all drink a lot and puke.

I can remember actively ignoring anything about the prom when I was in high school. I was soooo ready to just finish school so I get on with life.

^^^^

Nah, they’re just discriminating about food choice. After the fact.

We had an old cat. Grumpy curmudgeon that decided I was his human. We found out he had a thyroid problem, when he crawled up on my wife’s chest in the middle of the night, and pissed all over her.

So he was German ?

Is it bad I LOL’d?

Not at all, I was howling.

No, that’s poo. Peeing is more of a British thing.

OT: With one dietary change, the U.S. could almost meet greenhouse-gas emission goals.

TW: Atlantic.

I love how all the plans are “So simple”. It’s just one habit that should change. Sure it means getting rid of a staple of the American Diet, and one that provides important nutrients, the

communisterm… Green Revolution require it.I assume that the change isn’t to stop feeding the greedy maw of government?

It’s even easier than that, if we just kill everyone in Asia, Africa, S. America, and maybe Oceania, we’ll be fine.

I can see the Think piece:

US has thousands of Nukes. Why not use them to save the environment?

Cool link, bro.

Sorry, no nukes found.

Eastasia?

On balance, it would probably be better just to kill everybody who screeches about climate change – fewer killed in the long run. less disruption to human civilization, and they would be about as happy as they’re gonna be anyway.

And if it actually happened they’d just move the goalposts.

Nobody needs anything other than bean paste and water. I mean, it’s for the earth. You don’t hate the earth, do you?

Soylent Green revolution?

STOP CLIMATE CHANGE WITH THIS *ONE WEIRD TRICK*

The Green New Deal calls for getting rid of cows because of the cows’ gaseous emissions, but the increase in human gaseous emissions due to an increase in consumption of that food is OK?

I thought somebody here recently linked to an article that claimed people turning to vegetarianism would not have a significant effect on CO2 emissions.

They want to say that if 300,000,000 Americans switched from beef to beans there would be less methane emission?

Or what DnT said.

/sksksk and I oop?

I really hate Mojo for even mentioning it

Googled that, and one of the suggested questions is “what does i oop mean, in text?” “In text?” WTF?

Maybe you need to be a 13-year-old girl to understand it.

Tres Ver. 2.0 is approaching adolescence. I was gonna say “there’s no way Id put up with that!” but we had the Valley Girl thing.

Lots and lots of VG influence in the VSCO.

Bitchin’!

I suppose the thing that puzzles me most, particularly in that video, is context.

When do you “sksksksk” and when do you ‘and I oop’?

every 3 seconds apparently

Yeah, I live in that very Valley. The song was hilarious to us, because it rang so true.

This doesn’t seem that different honestly.

Yeah, it’s like Valley Girl meets eco-anxiety.

you’re done…..

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t79TwDS2dVA

Yeah, that seems worse, but maybe it’s just because I’m 53 now. I bet the valley girl thing would be just as offensive to me now, Especially the cheerleader knee pop walk thing. That was worse than the vocals.

Just as offensive? You sure?

/evil grin

She’s a caricature. Actually, most girls did some of this sometimes, back then. In the valley. The song kinda put the brakes on it, because they would get ridiculed for it. Every little VG-ish thing got mocked and blown up. The whole group would start with the OMG, fer sure, fer sure routine. Eventually, every one just avoided even hinting at it.

I’m sure the VSCO thing will go the same way and much faster.

That made my brain sad for her brain.

VG related: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LuN6gs0AJls

I hate how that song overshadowed the much better album around it.

*makes note to listen to full album*

Just to be clear, that is a great song.

The rest of the album is better, and in a different way. More “interesting”, perhaps. Not so obviously looking for a “hit”. I would not be surprised if the record company made them put that song in there at the last minute. (Used to happen all the time.)

Oh, do not start an 80s nostalgia cascade!

Why not? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1UYDKxxQ50o

Because I have to work and I’ll get lost down that rabbit hole!

Karma’s a bitch, Mojeaux

Good song. Here’s one in the same vein.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k5JkHBC5lDs

Or this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ejorQVy3m8E

I hate the way that song overshadowed the better five albums and two EPs before it.

Hah!

To be fair, that was the first album I acquired. But I was familiar with some of the earlier stuff once I went backwards and acquired that too thanks to the kick-ass radio station I listened to back then.

Here’s one for the Gingers.

Well played

LOL!

It means you are old.

I dealt with “phat” “sick” and “fly” I watched rap music rise out of the dayrooms of the nation’s county jails, the snively whiny grunge trend, the slacker thing in the nineties and now the retardation of the millenials. I ain’t afraid of some two bit vsco girls.

You are going to be so sorry you asked.

That girl! If her parents saw that and chose to hold her down and beat the VSCO out of her like some weird 80’s de-programming thing? Id say “thats wrong!”

But….I’d understand

She’s got almost 1,000,000 views. I’d beat her if she wasn’t raking in the cash hand over fist.

She’s monetized?

Don’t know. If she weren’t, she’d have some splainin’ to do.

to whom?

Me!

“Child, why have you not monetized your channel?”

“I dunno.”

“Do it! Now!”

Mom! No one likes me!

“sksksksk” and “and i oop” died last week! Can we still go to Sephora?”

Not woke.

https://hotair.com/archives/karen-townsend/2019/09/26/brewing-company-honors-carson-king-puts-critics-shame/

Because of course.

WTF is wrong with this country?!

Oh. You’re one to talk…

*snort*

alleges to have received…

Oh well, I suppose it is unfair to insult the grammar of someone who is making an allegation. Unless of course everyone discussing it is a freaking ‘journalist’.

I can’t believe that the beer company dropped their connections with him. Talk about chickenshit

Buncha cuntes! Dude’s single handedly creating boucoup bucks for charity. Can we just applaud his efforts and graciously accept the help? No, we have to scour his twit history and proclaim him unclean. Fucking hate this trend.

Hungarian would be terrible for them; besides the definite and indefinite articles, verb conjugation had finite and indefinite versions. Oh, and you can end up with definite articles with indefinite conjugations and vice versa.

Language is weird when you stop to think about it.

Is finite and indefinite verbs like the verb aspects of Slavic languages?

I’m not familiar with slavic languages, but it looks similar.

As an example, “Olvasok egy könyvet” would translate to “I’m reading a book” and “Olvasom a könyvet” would be “I’m reading the book”. Egy is the indefinite article, and a is the definite, but the verb olvas gets conjugated to match, with ok being indefinite and om being definite.

No; it’s something completely different from verb aspect.

Roughly, imperfective aspect is ongoing or repeated action while perceptive is one-time completed action. So there’s no present tense in the perfective aspect, and almost every verb has both aspects.

Way too difficult. I have no idea how a non-native speaker could learn Russian.

When I studied in St. Petersburg, a bought a wristwatch. I wanted to make certain it was a line-up, since I didn’t want to have to deal with Russian batteries I’d never be able to find in the US. So I looked up the verb for winding a watch… and then I had to think which aspect to use. Finally I realized, “Do I have to wind it every day?”, because the “every day” clearly necessitated the imperfective aspect.

I spent about $6 on the watch, which lasted a good ten years. I had to replace the band twice back in the States, and each time spent more than I spent in the watch.

I heard „Deutsche Sprache, schwere Sprache“ a lot in Germany.

Everyone thinks their own language is the totes hardest.

Hungarian has over 30 noun cases, depending on what you consider a grammatical case. Every language has at least one seriously complicated thing; Russia has verb aspects, Japanese has their honorifics, Welsh has a chronic fear of vowels.

y is a vowel

And then there’s aspect in the imperative, which is a whole different can of worms. I think that’s why you get the stereotype of Russians saying things like “Please to be speaking more clearly” (the progressive tense).

Ah, no, that is different. Verbs are generally fairly simple in Hungarian, there are only three tenses and the definite and indefinite forms, and very few irregular verbs. Nouns, however, get hammered; your examples of imperfective and perceptive would be indicated by noun case in Hungarian on the object.

That’s one big difference between Japanese people and Chinese people speaking English; Japanese mix up “a” and “the, but Chinese don’t even try use either.

“I don’t know whether or not (the Democrats are) going to have time to do any deals. We were working on guns, gun safety”

Donald John Trump, 45th President of these United State

Why is it that when these assholes talk about doing deals it is always us that pays both sides of the deal?

What’s the difference between a politician and prostitute?

The prostitute takes your money after fucking you.

That’s world class trolling.

England is killing the Eagles with scrum play.

You didn’t expect the US to be in this game, did you?

They certainly weren’t this morning.

Ok, so why is it “oshiko” but not “ounchi”?

Less honor for #2!

Not terribly long after I reverse Tron’ed into this walking carcass, I was waiting tables at a sushi place and taking a Japanese course b/c I needed a language credit for my degree.

The Chinese also working there always made fun of me (sad trombone) when I tried to speak Nihongo as I apparently spoke like a little girl. The American teacher apparently only learned little-girl speak and passed it on to the students.

Made fat stacks working there, though. Good times.

Once again I read the title as Learn Japanese Through Anime Tiddies. *hangs head in shame*

https://youtu.be/tA1cZOdGtLs

Those anime tiddies aren’t exactly “fat”., Gustave.

I don’t like anime.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=AURl5fxmkoA

I can’t really get into it myself, although I did like it when I was younger. Came across that one not too long ago and the ridiculousness of it stuck with me. Japanese witches with jet packs fighting in the role of the allies in a WWII-esq war.

damn that looks stupid. makes me think the Anime I watched back in the day was no real anime.

While I find these quite interesting, with each one I read I want to learn Nipponese less

How do you say “yo momma so fat she could be two sumo wrestlers”?

あなたのお母さんはお相撲さん2人のように重いです。

Wouldn’t be funny, though.

I mean it’s not funny in English, so that’s okay

Also good morning glibs. Yes, I will ignore the college football thingy that was posted.

https://www.oregonlive.com/nation/2019/09/the-ok-hand-sign-has-moved-from-trolling-campaign-to-real-hate-symbol-civil-rights-group-says.html

Japanese white supremacist duo WINK! hit hardest.

??

?

https://www.oregonlive.com/news/2019/09/2nd-oregon-death-in-vaping-related-severe-lung-illness-announced.html

Where’s my shocked face? The carpetbagging big gov RINO representing the Califucktards is begging the gov to ban vape product sales.

There is no legal “cartridge[…] compatible with Juul devices”.

God the fucking lying going on here is epic.

So since we’ve been talking about grammar today…

Ouch