It was warm for November, at least by the standards of most of the men who had just arrived at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, for the pending Trans-Atlantic voyage. The temperature on November 2, 1944, was in the mid-fifties throughout the day, even made it into the sixties. Two transport ships – the MS John Ericsson and the SS Santa Maria – waited at a pier not far away in New York, both bound for England and the War. The men, most of whom hailed from Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey, spent a comparatively idyllic twelve days in the area, using twelve and twenty-four hour passes to visit the Big City. The average age of the men was twenty-one. At least one of them came from the small town of Johnston, in the smallest state, Rhode Island. That was my grandfather. If he was unusual, it was only by his comparative age: his twenty-fifth birthday had passed a week earlier and at home waited a wife and three children.

The 272nd Infantry Regiment officially became a part of the 69th Infantry Division on May 15, 1943, with its activation at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. The original cadre of 23 officers and 228 enlisted men came from the 96th Infantry Division at Camp Adair, Oregon. By the time the unit received its reinforcements from the Northeast and finished training in Mississippi, it was “the Fighting 272nd, the Battle Axe Regiment,” under the command of Colonel Walter Buie, United States Army.

The men sweated under a special kind of nervous anticipation; it comes only from knowing you are headed to War. There is some of the bravado often associated with high school sports, as young men fall back on the only remotely analogous contest-of-wills they have ever known. The thoughtful ones are almost always quiet; they know that sports do not contemplate Death and Destruction as their ultimate objective. Despite this, however, optimism reigned.

While the War in Europe was raging, it had been turning steadily in the Allies’ favor. Even the Japanese were beginning to lose ground to the U.S. in the Western Pacific: in early October, the Allies landed forces on Crete; Canadian forces crossed into the Netherlands; and the Soviet Red Army entered Hungary. By mid-October, the first battle on German soil – at Aachen – began. On October 20th, 1944, MacArthur landed in the Philippines to announce that he had returned, good to his word.

By the time the men of the 272nd make it across the Atlantic and establish their headquarters near Salisbury, England, the war appears to be firmly in hand for the Allied powers. It is now being fought on the German homeland; the men of the 272nd are almost jovial as the word gets to them about the course of events.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

“Fraaann-cisss!” The kids yelled my middle name as a taunt. I tried to hide in the bushes, but they know I’m in there. Every day going to and coming home from school is like this. It’s a girl’s name some older kids say. Fraaann-sisss. It always came out that way. My first name – Dale – hardly made the case against me any better. The kids who do it are older, bigger, and worst of all, they come from money. Their family name is on local stores. I curse them from the bottom of my soul every day, wishing them horrible misfortune. Years later when passing through town I notice the stores have changed names. I ask around and learn the family suffered terrible tragedy and lost everything; the feeling of schadenfreude that comes over me can only be described as decadent and sinful.

At some point I remember asking my father why my name was what it was: just why (oh why?) did you name me this, Dad?

“You got your first name from my Staff Non-Commissioned Officer in Charge. He was a really good man when I was young Airman in the Air Force. His name was Dale. And, of course, your middle name came from my father, your grandfather, Francis Norman Saran.”

None of that meant anything at five years young.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

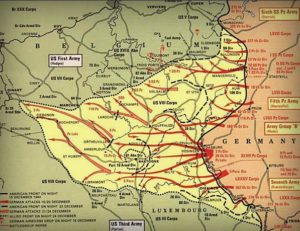

The morale in the 272nd whipsaws on December 16, 1944 when the German Army launches a massive counteroffensive into the Ardennes forest in Belgium, beginning what will come to be known as the “Battle of the Bulge.” The German military had used the exact same tactic in the exact same place three times previously – September 1870, August 1914, and May 1940. Despite this, the Allies leave the Ardennes lightly defended by two inexperienced and two battered American divisions and the Germans catch them flat-footed. Three German armies – more than 410,000 men, along with all of the supporting arms – launch the deadliest and most desperate battle of the European campaign in the heavily wooded, rugged terrain of the Ardennes. The once-quiet region is overrun with the German counter-offensive. The 1st SS Panzer Division takes the town of Malmedy on December 17, 1944, and eighty-four U.S. soldiers are executed in the Malmedy Massacre. The U.S. 106th Infantry Division will be decimated before the battle’s end, as it seeks to buy precious time for Patton’s Eighth Army to execute an impossible ninety-degree pivot from the town of Lorraine to protect the American flank at Bastogne.

The Wehrmacht, led by Hitler’s own disciple, Sepp Dietrich along with SS Troops, penetrates the Allied lines along an eighty mile front. Only at Elsenborn Ridge do the Americans hold. The possibility exists that the German Army will run all the way to the Belgian coast at Antwerp – that is indeed Hitler’s plan – severing the line between the U.S. and British forces and leaving four entire Allied Armies trapped behind German lines. The hope for the Germans is a separate peace with the Allies and then a chance to fight their arch-nemesis Russia – alone – on the Eastern Front.

My grandfather’s unit yearbook grimly records the events:

Morale was high, and war seemed to be far away during the first part of December. Then came the newsflash of the German breakthrough in Belgium on 16 December 1944. War now seemed close at hand, and our attitude changed from one of the casual interest to one of serious personal regard. On Christmas Day, 700 men were taken from the Regiment for immediate shipment to Belgium to help stop the German onslaught. It was about this time that the Regiment was warned to prepare for shipment to the battlefront. During the remainder of the cold days of December and the first part of similar January days, we continued to train and readjust from the Christmas Day losses.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

My father leaves the Air Force in 1968 while the Vietnam War rages on; we wind up near his sister and I am born in a small town in Eastern Texas. That doesn’t last during the tumult of civil rights marches and desegregation and my mother home alone with two infants. We move back home to the Northeast – back to the home my father helped build, alongside his father and brothers: my grandfather’s house.

We don’t stay there long, but my early childhood revolves around my father’s parents and the family headquarters, as it were, on a small plot in Johnston, Rhode Island. My grandmother, the family matriarch, presides over the chaos of her six children with all of their kids, while my grandfather is the very definition of the kind, gentle Stoic in the midst of it all. His pipe smoke – first Borkum Riff, later Captain Black Apple-flavor – are like incense in the front room, where he can be found staring out the front door into the trees beyond the driveway. He stands like that for long moments, for what seems like forever to my young eyes, and I can never figure out what he’s seeing.

The Red Sox are always on in the background, either on the television set if we can get reception with the proper combination of rabbit ears, tin foil, and luck; or on the radio, if none of the above coalesce for visuals. On Sundays, my grandfather attends the church where he helped lay the cornerstone. When he returns, we all know we’re getting “dough-boys” – Pèpè’s special “recipe” of bread dough with a whole cut or ripped in the center, fried in some oil. Every once in a while he’ll gift us with french toast if we beg.

He smiles, his blue eyes clear and twinkling, never looking past you, always right into yours.

“Alright, my boy!” he says with unadulterated enthusiasm. “Here we go!” as he puts the plate of steaming fried dough on the table and we all chafe to cover ours with whatever we like: my father eats his with butter and jelly, carefully preparing each bite, while my sister and I rip the dough into pieces, lightly burning our fingers with impatience, and then slathering the bits with maple syrup.

My grandfather always sits patiently at the table with us, or hangs around the kitchen watching us eat, a smile across his face. He listens, watches, sometimes participates in the conversation, but always smiles watching us eat. It doesn’t dawn on me until decades later that having been born in 1919, his childhood would have been right in the middle of the Great Depression. Once over some holidays one of my grandfather’s brothers comes by to visits and I hear the adults in the kitchen from where I am snooping, just outside of the threshold:

“Remember those lard sandwiches, Frank? We used to take those to school every day.” Everyone turns to my grandfather – I can hear it by the silence.

“Oh yeah,” he answers evenly. “Yeah. Every day…” The other adults – my father’s generation – turn to my great-uncle and urge him to explain.

“Mom would cook the bacon in the morning,” he begins, “and then when it cooled to a solid, she’d put that right on some bread and that’s what we brought to school: lard, with some of those bits in it, on bread.” You can hear the recoil and disgust from my father and his siblings. I cringe where I’m standing.

“Ehh, I didn’t think it was so bad…” I hear my grandfather’s voice into the silence and the room erupts in laughter and jeers. My grandfather almost sounds sheepish, but it’s so genuine I’m filled with sorrow for him, though I can’t quite articulate why in my six-year-old mind.

Later, I realize that my grandfather is the only person who could express such simple, genuine gratitude for eating leftover lard. He doesn’t know how to be ungrateful.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

The 272nd is rushed to the front in January of 1945, while the Allies try to hold the bulge in the lines and contain the German break. The Regiment crosses the English Channel during a blizzard. They land at Le Havre on D+189. The 3rd Bn Commander recorded their rush to the lines in his reports:

The remark, “That truck ride,” will never refer to any but the one from Le Havre in open trucks. “Standing room only” and “Destination unknown” are both understatements, although the application is sufficient. If people scoff at your tale of standing on only one foot during an eight-hour ride at night in a blinding snowstorm while the convoy was lost, any doctor will admit it is possible if the near-corpse is frozen stiff.

Leaving the Château de Vallalet, an 18th-century edifice that had seen rough usage under the Boche occupation, and the surrounding area of Romescamp and Gaillefontaine, the Battalion squeezed into boxcars that jerked along for days. No fiendish torture device could have left the Battalion’s body in worse shape. At last, the arrival was made at port, and the historic events of the present 3rd Battalion began with a muddy boot, a sloppy tent, and the foreign sounds of “Oui, oui” and “Cidre.”

Those ‘foreign’ sounds would have been native to my Quebecois grandfather. I imagine him quietly speaking the pidgin French of his ancestors, and of his wife (née Messier), who used to switch to the French whenever she didn’t want the kids to know what she was saying. We were raised in an English-speaking household, but it frequently swore in French.

By the time the 272nd reaches Belgium, the German offensive has spent itself. The Wehrmacht Army has run out of fuel, men, and momentum, in large part due to heroic losses sustained and inflicted by the Americans in thwarting the blitz. The defense at St. Vith, at Elsenborn Ridge, and famously portrayed at Bastogne, coupled with Patton’s impossible 90 degree right-wheel of his entire 8th Army, is enough to hold the Allied defenses. My grandfather’s unit now moves forward to confront Der Fuhrer’s Army as it pulls back to its defensive positions at the Siegfried Line. The 272nd, along with its sister units, will have to punch through it to finish off Hitler’s war machine.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

After I complete Officer Candidate School, I pass by my grandfather’s house just to say hi. I visit far less than I should and rationalize it a million ways, but the truth is that it’s because they are old – like, really old, and I am young. I don’t know how to talk to them. They want to reminisce about the child I was… while I am trying desperately to prove that I no longer am. I want to talk my upcoming commissioning as an Officer of Marines, Leader of Warriors…

“My boy, whatever you do, you don’t volunteer for nothing, okay!?” My grandfather is serious. “I am telling you. Whatever you do, you don’t volunteer for anything, okay?”

“I promise, Pep. Not me.” I make a solemn vow.

“The only thing I ever volunteered for in the Army…boy, they got me, I tell you.” He jabs in the air with his pipe for emphasis. He shakes his head and I can see he is looking somewhere far away, somewhere I haven’t been…

He looks toward the television set, but it’s turned off.

“We came back from a long march and boy, I tell you, was it hot in Mississippi!? Whew! With our packs and rifles…” He shakes his head at the memory. “The drill sergeant got up in front of us and said, ‘Okay, is anyone here tired? Does anyone want to volunteer for a different job where you won’t have to carry your pack and rifle?’ My boy, I was so tired… and I’m a little guy!”

My grandfather turns to me with his eyebrows raised. I laugh because at 5’9″, he’s three inches taller than I am, but I know what he means. He is still healthy at 80, but he slight-framed, always has been, unlike his own sons, who are tall, broad-shouldered, and thick of chest and limb.

“Those packs and rifles and all the stuff they made us carry… it was so heavy!” It is the infantryman’s lament and I have had a nice heaping spoonful of it over the last weeks, but I shut my mouth out of respect. I know where he has been and where I haven’t.

“So…so I looked around and I says, ‘Sure! Sure thing Drill Sergeant. I’ll do it!’” My grandfather stops staring, turns back and looks at me, genuine surprise in his eyes, like he still can’t believe this happened.

“I stepped forward, and the Sergeant said, ‘Okay. Now you’re now a bazookaman. You carry the bazooka.’ And I knew he got me. Boy, he sure got me good.”

I laugh out loud so hard that it comes out as a bark, myself having just returned from a summer at the hands of Marine Corps Drill Instructors. As I look into his eyes, however, I can see, my blessed grandfather is and was genuinely hurt by that. He was, and maybe still is, that trusting. He cannot believe his Drill Sergeant pulled one over on him like that.

“So don’t you volunteer for nothing, my boy.” He says, pointing his pipe at me. It’s the final word on the matter. I enjoy his presence for a few minutes while he puffs and stares peacefully, the clouds of smoke with apple and spices float over, and I try to be as patient as a twenty year-old can be. I want badly to ask him about what that was like, but I just can’t bring myself to do it. The gap is too wide; the chasm too deep… I don’t know how.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Nevertheless, a night in the woods isn’t housing, and nothing short of a steam radiator could have made the bivouac area among the Belgium firs a comfortable one. These were the most miserable of the bad nights spent. Foxholes were to be dug, but the spadework never passed the slit trench depth. The ground was frozen, and even all the ponchos and blankets that could be mustered were little help. Teeth still chattered between fits of sleep. Moreover, the puddle in the bottom of the hole got deeper and deeper. Nevertheless, it felt less damaging than the wind that blew overhead.

One night, the darkness was so intense that men wandered away towards both the enemy and the rear. Pfc. Arnold of B Company walked 10 yards from his tent and spent the next 15 minutes trying to get back. Guard reliefs that night were unreliable, too. Even when the relief was to be called by the guard himself, there was no certainty that his tent could be located. Just before dark, S Sgt. Slaich carefully marked the path he was to walk to awaken the next guard, but two hours later, that path was invisible. After an hour’s fruitless search, with nothing to show but scratched hands and face, he returned to his post and the easiest choice – to take the next guard shift.

“But those nights weren’t the worst,” Pfc. Nyland constantly repeats. “I remember a short jaunt of 13 miles we were to take through the woods one afternoon. Trucks were to pick us up at 2 o’clock. We were waiting beside the road long before that time rolled around. About 9 o’clock that night, the buggies finally arrived. It was raining harder than I’ve ever seen over here, and the wind blew it cold into our faces.”

“After the duffle bags were thrown into the truck, we piled on – 25 of us with our packs on our backs. I sat on top of the cab, where I thought I could find plenty of room. But when the rain came down harder and it grew colder later that night, I regretted that move. To keep warm, I cursed everything connected with the Army, with Europe, and with winter warfare.” Those 13 miles took 12 hours to cover, and the rain never stopped as long as the ride went on. –History of 1st Bn, 272nd Infantry Unit

My grandfather carried a bazooka as a member of “King” Company in the 3rd Battalion, 272nd Infantry. I’ve stared at the picture that has his name underneath it and no matter how hard I try, I can’t tell who he is. The picture is black and white and the men are too far away to see more than dark slits for eyes. There’s a large building in the background with “Apotheke” on it – the German word, derived from the Greeks, for “Pharmacy.” The men are in neat rows, like every military picture ever taken or painted, row upon row, tallest in the back, shortest up front, and somewhere conspicuously out front or at the sides are the leaders… but this is an after picture, of that there can be no doubt. These men are different than the men who started in Le Havre…

On moving into positions opposite the Siegfried Line, the Battalion climbed the muddiest, steepest and longest hills in our history. The going was so rough that walking on knees was nothing unusual. Even though there was a possibility that the shoulders were mined, everyone had to stop for occasional breaks on the way up. The entire Battalion started off in regular formation, but within an hour each company was spread over at least 800 yards. In another month, though, the troops were to wish that they could have gotten that much dispersion.

At Kamberg, the Battalion received its first real baptism of fire, with no wish remaining for further communion. The troops were told what to expect and what to look for by the group being relieved. They gave constructive and helpful advice. This in itself gave everyone a feeling of confidence; the men were getting first-hand information from the boys who knew.

The first day there, a patrol of Lt’s Cox and Young, Sgt Johnson, Pfc’s Hagquist, Fulcher, and Schellman of King were pinned down by mortar and 88 fire. Two days later, 2nd Lt Entzminger, leading his 1st Platoon patrol, was caught in the crossfire of two pillboxes. The Lieutenant observed the enemy position 200 yards to his immediate front and, upon ordering his patrol to withdraw to safety, he remained in a forward, exposed position, calling for and adjusting artillery fire upon the enemy pillboxes. Although subject to danger from friendly artillery as well as enemy small-arms fire, he remained in the position until after the supporting artillery barrage was lifted. Immediately after the barrage, while shifting his position, he was mortally wounded by enemy small-arms fire. Two others were wounded, and several men of the Platoon distinguished themselves by their efficient and courageous leadership.

Immediately afterwards, 1st Lt Coppock was ordered to take out a Battle Patrol of four enlisted men to determine the strength of the enemy in the immediate front of his position from which artillery, Nebelwerfer and intense machine-gun fire were being received across the entire Regimental front. Lt Coppock* pursued his task with such vigor and disregard for danger that, during the night, he succeeded in penetrating 1,200 yards from the Siegfried defenses into the enemy position. Having collected the information he sought, he then led his patrol safely back with vital information necessary for military operations. As a result of 1st Lt Coppock’s action and report, a decision was reached in higher headquarters that greatly accelerated the advance of our troops through this sector. –History of the 3rd Bn, 272nd Infantry Unit

(*) Lt Coppock won the Silver Star for his actions, the 3rd highest award for valor in the U.S. military

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Life in the military takes me away, as it does to everyone who makes it a career. We move our own young family all around the country and the world at the whims of the Marine Corps and my career. Holidays are a chance to reconnect, but with not a lot of leave on the books and a passel of kids to bring along, we rarely see my grandparents. I spend some time off of the Bosnian coast in 1995 during that unpleasantness. We hear the war, read it intel reports, study it, study the geography, plan routes, even rescue an Air Force pilot, but we don’t see the war… We don’t live it. At the time, the notoriety of the rescue and the relative dearth of conflict gives us what we think is “cred.” People chase “red ink” – combat time in pilot logbooks is logged in red ink – because we are fools.

I talk to my grandmother about that 6 month deployment aboard ship. She’s lamenting the time away from my kids and then she makes a backhanded comment that pulls me up short.

“I remember when your grandfather was away at the war…” She begins.

“Oh? Really? What was it like?”

“Ohh, he used to write me all the time… Such letters! Oh. Your pèpè, he would send me such romantic letters…” She exaggerates the word to the point of absurdity. I laugh.

“How long was he gone for?” I ask.

“Ohhh…psshh… I think about three years or something like that…?”

Gulp. Holy shit.

“Saving Private Ryan” comes out in July of 1998. I am in law school at the time with four children. By the time the Bar is over, and Naval Justice School completed, we have orders for Okinawa, Japan and are gone the day after I swear into the Bar. I finally see the movie at Marine Corps Air Station Iawakuni, Japan, while working on a case with a colleague and friend. I am as awed by it as every other American seems to be. It is an amazing movie and I vow to talk to my grandfather about his service after seeing it.

When we return from Okinawa for Christmas of 2000, we visit my grandparents. I want them to meet our daughters, so we trek the whole carload up those same roads of my childhood. Except now the woods seem impossibly thin, the distances far shorter than I remember, the driveway and the big spruce in the front yard… are not very big.

At some point my grandfather is standing by the door, talking to the parakeets in their cages, whistling to them while they chirp back. They know his voice and always respond when he talks to them. Outside the wind whips at the screen door.

“Hey, Pep?” I am sitting in his chair.

“Yes, m’boy?” He looks up from the birds and smiles.

“You hear about that movie – ‘Saving Private Ryan?’” He squints at me and then seems to finally have heard my question.

“Oh. Yeah… yeah, I did.” He stands up and puts his hands in his pockets, fumbling with some change and walks to the door.

“Would you like to go see it… together… uh, with me?” He never turns around, and he talks at the door, but I can still hear his voice today, like he’s in my room right now.

“Naaaahhh, my boy… I don’t wanna go see that… I… I seen all that already.” He turns back to me and smiles, but his eyes are pinched at the corners.

The shame washes over me. What an arrogant thing to ask, to assume… I regret asking that question to this day.

Third night at Kamberg was the busiest for the outpost. At about 2130, the King (K) Patrol returned, bearing two casualties. About midnight, the demolitions patrol of T Sgt Farley came by the OP (Operations Post) for last-minute instructions before jumping off on their attempt to blow up the pillboxes. The patrol soon left and returned about 0300 with their mission accomplished. The outpost had front-row seats for this exhibition, and can testify that those boys did a good job.

In addition, Item Company is justly proud of its Aid Men. Their deeds shine brightly through the darkness as memories take the place of battle life. One day, as mortar shells were coming in pretty thick, Jenkins of Item was wounded. Out there could be seen the figure of a man running swiftly and without hesitation – Mike DiCubellis. A medic was needed, and mortar fire or not, Mike was going to where he was needed. In just a moment he had reached the fallen Doughboy. Working feverishly in a field where individual movement meant danger, the Medic never flinched, seemingly not realizing that death flew through the air with each burst. After the engagement, he remarked, “Didn’t have time to dig in. The guy was hurt bad; had to work fast.”

The Communications Section must be praised especially for its fine job at Kamberg. Although harried by mortar fire day and night, the lines between the rear and forward CPs and each line company were in service at all times. The whole week at Kamberg was, as one man put it, a thin solution of night. We were like owls, having eyes only for darkness.

Leapfrogging nimbly over the last perimeter of the Siegfried line, the Battalion took Dahlem, our first town, in a walk – literally – and what a walk. The troops were loaded down like a convoy of one-man bands. Mind you, at that time, it was mostly GI equipment, not boodle!

Leaving Waldorf, the Battalion went on First Army Security Guard al the way to Stolberg and Aachen, big cities wrecked by American bombing. This meant working with engineer guards with white SGs on their helmets. This was the Battalion’s chance to get in on some of the luxuries of rear echelon – beer, movies, showers. That good deal was over in five days, and the Battalion crossed the Rhine in trucks on the 28th of March.

Arriving in the ancient town of Arzbach near the Lahn River late at night, the Battalion settled down for a few days with little action except intensive patrolling of the area. For the next week, the Battalion moved by vehicle or foot from town to town, trying to catch up with the Krauts. Leaving the town of Dehrn, which is memorable for the 100 slave workers who were living in a lice-infested seven-room house, the troops rode the TDs (Tank Destroyers) and other vehicles 100 miles to Lohne without incident. The second day at Lohne, the order came for a march to Altenstadt and surrounding villages, a 10-mile jaunt with full field and boodle. Everyone soon swore off, “No more loot.”

An early call the following morning started the Battalion on its unforgettable 28-mile march to Kassel, even though aching and blistered feet characterized the day. The men made it, however, and pulled into Bettenhausen on the outskirts of Kassel. Nevertheless, boodling that night took sheer guts. The troops had not been so exhausted since the aftermath of forced marches at Camp Shelby. –History 3rd Bn, 272nd Infantry Unit

* * * * * * * * * * * *

My grandmother and grandfather’s wedding picture hangs on their wall, as it always has. When I was young, I once looked at the picture and asked my mother, “Who are those people?” I could not reconcile the young woman in the picture – blonde-haired, blue-eyed, and statuesque – 5’10” anyway, with the woman in the kitchen smoking Virginia Slims – imagine Ursula from “The Little Mermaid” with a flower print dress … but my grandfather is unmistakable in the picture. I know the look on his face – I recognize it instantly – because I’ve seen it reflected back at me in the mirror before; he is crazy in love with that woman next to him…my grandmother.

Sixty-four years later they’re still together, but now the dementia or Alzheimer’s has left my Mèmè, the powerful matriarch, a shade of her former self. She has been in and out of the hospital and ultimately is back in the house at my grandfather’s insistence. The last time I was there, she had about 10 minutes where she recognized me and we were able to communicate, but now… now she has only one word. She rocks back and forth and calls my grandfather’s name: “Franny. Franny. Franny.”

“I’m right here.” He pats her hand and smiles. She only stops when he touches her, or talks to her, or coos at her, like the birds. I realize in that moment it’s not what he says, it’s how soothing his voice is, how much love he outs into the sounds. It’s like baby-talk, but this isn’t cute or funny, or self-aware at all; it’s a man trying to convey over 60 years of love while he watches his wife dissipate before his eyes. Fifteen minutes is almost more than I can take, but it’s not her calling “Franny” that affects me: it’s being present. I feel like a voyeur. This is theirs and theirs alone.

My grandfather and I talk about the Red Sox, our family history – his family history – and he mentions that he is the only one left. I’m not sure what he means.

“Of my brothers and sisters… I’m the last one,” he says.

“How many brothers and sisters did you have, Pep?”

“There were twelve of us.”

I can’t fathom any of that; not eleven siblings, not growing up in the Depression, not carrying a bazooka in World War 2, and not outliving all of my family at age 82.

I just stand next to him and put my hand on his shoulder while he looks outside.

My grandmother passes while I am in training to go to Afghanistan.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

The 272nd Infantry Regiment’s history is a surreal walk through war, told by the men who lived it. There is the time the 3rd Battalion gets shelled by German artillery after crossing the Werra River and takes shelter in the basement of a building… that turns out to hold cases and cases of wine and French champagne. Two men are killed and three wounded, but the 272nd pushes on to Eichenberg. “Love” Company takes the town and King mops up.

They push on toward a town called Nieder-Gandern, but receive Tiger tank fire beginning in a town called Hebenhausen all the way to their objective. Even after they take Nieder-Gandern, the Tigers never stop their fire and four men are killed during the night and morning. A German night counter-attack is repulsed at close quarters.

Early the next morning, the Battalion bypassed all the dead Krauts who had counterattacked during the night. King Company led over a circuitous route, through the woods and onto the road. One sniper was flushed out by the lead squad under S Sgt Smith, Sgt Jonassen and Pfc Tarkington, and in the second town, 21 men were captured and 10 wounded or killed. The light machine gun section of the 4th Platoon of King accounted for one man. Along the way, M Company caught a group of the Boches running up a hill. The HMGs (Heavy Machine Guns) gave ‘em the hot foot, and the Company proceeded unmolested, leaving behind over a dozen dead Krauts. That night was spent in almost forgotten comfort, complete with soft beds and electric lights in Heiligenstadt.

Bad Kösen. Naumburg. Kottochau. The names of towns tick of as a checklist of objectives. The Regiment continues to pursue the Wehrmacht ever deeper into German territory. At Thiessen, the Regiment narrowly avoids walking into an ambush when a patrol discovers some wounded Germans from a nearby village, who explain that Thiessen is going to be a “last stand” for that unit. The Regiment hastily forms up and attacks the German 88mm dual purpose machine guns emplaced in the town. There are 36 of the anti-aircraft/anti-tank guns, which are considered among the best guns ever made, given their ability to take down allied aircraft or destroy allied tanks. The 272nd catches the German gunners by surprise and, along with some excellent gunnery from supporting artillery, it takes 249 enemy prisoners.

Germany’s 5th largest city, Leipzig, is the next target on the Regiment’s checklist. It takes hand-to-hand combat, but the 272nd captures a German barracks, and over the course of a day and night of fighting, another 234 enemy soldiers are captured.

The activities were climaxed the next morning when a feminine voice was heard rendering some smooth English. The voice belonged to a gal from Boston named the Countess de Maduit, the former Roberta Lorrie of Boston. She could not believe the Yanks were there until a few cuss words cinched the fact. The perfect portrait of an overjoyed woman, even though she bore the scars of an unforgettable past, she showed Love Company the concentration camp. Tears rolled down the cheeks of the men as they were shown the sea of people subjected to the barbarous treatment. The worst came when they saw what remained of a building the SS had burned to the ground. To keep the record of the Krauts straight, they had crowded some 200 patients into it before igniting the fireworks. The sight was not a pleasant one. The troops realized that the enemy was all and more than anyone had ever imagined.

It is not long after that the 272nd makes contact with the Soviets coming from the east. The German Army is vanquished.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

When the Red Sox come back from three games down against the Yankees and win the American League Pennant, I have to choke back tears. I am in Afghanistan at the time. The tears are not for me; baseball has never been my love the way it is for my grandfather. I break protocol and sneak a phone call; I can dial the number to my grandfather’s from memory. His 85th birthday is just weeks away and now, one year removed from another Yankees heartbreak that I thought might kill him. I know the Sox will beat the Cardinals. They have to.

I hear his voice over the scratchy connection.

“Hello?”

“Pèpè? Hello? It’s me, Dale.”

“Yes?” We step on each other’s voices because of the delay, but finally I can hear his recognition that it’s me. I start shouting like a fool.

“They did it, Pep! They did the impossible!”

“I KNOW IT, MY BOY!! I THINK THEY’RE GONNA DO IT THIS YEAR!” I can hear the joy in his voice. I look around to see that no one is there and I let the tears run freely down my face.

He was born the year after they won their last World Series (1918) and he has watched eighty years or more of Red Sox tragedies, one piled upon another. He has borne it all with a patience that would make Job nod in approval. I’ve endured a good deal of it with him and never, not once, have I ever heard him swear. Not a single curse word. We watch Bucky Dent rip our hearts out in ’78 and all he does is throw his hands up, look at me in complete disbelief, and turn off the little black and white television set. He walks to the door and stares while he puffs away. I come to hate the Red Sox for the pain they inflict upon him…

When they sweep the Cardinals in ’04, I almost don’t care if I die in Afghanistan. He finally got to see them win it all. Finally.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

By the time my wars have ended, the Red Sox win their second World Series and when I visit my grandfather, we discuss Mike Lowell for governor of Massachusetts, the ’04 win… we relive our favorite parts in glorious detail. His sad-sack Patriots are now officially a dynasty and even the Celtics are looking good. Neither of us can believe this new world we inhabit.

He’s switched from a pipe to cigars, much to the chagrin of his children.

“I’m worried about these cigars he’s smoking,” says a relative about my grandfather’s new habit, to which I riposte that he is now in his late 80’s, and entitled to pick up a heroin habit, as far as I’m concerned… it’s no one’s business.

I happily indulge my Pepe with illicit Cohibas I’ve managed to get my hands on from a friend who is a ship’s captain in a country that doesn’t have an embargo on Cuban rum or cigars. I hate cigars, but we smoke them together in celebration. It’s the best smoke of my life.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Under the experienced command of Lt Col Edward J. Thompson, the 3rd Battalion of the “Battle Axe Regiment” had proven itself well in combat. Over hill, trails, and to the magnificent woods that spelled digging, smoky fires, makeshift shelters and excitement, the 3rd Battalion has caught in its wake of fire, memories that surround themselves with flesh and blood, with hope and sorrow, and with laughs and experience. During that time, a Battalion changed from a carefree, bivouac-inured herd to a confident, battle-tried team of fighting men. Only one medium can effect the change; only one process can bring about the metamorphosis. That one process is war. The actual struggle of meat and bone remains, as through the centuries, the unique method of shaping troops from the whims and idiosyncrasies of rear echelon to the positive qualities need to fight a battle. The way has been hard; it could have been harder. A spirited Battalion now exists that will function well under any conditions.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

A little while after my grandfather’s return from Germany, he and Meme conceive their fourth child – my father. A true “Baby Boomer,” he is born in the shadow of that terrible war. Twenty-two years after his birth, I am born in the shadow of the Vietnam War.

My grandfather lived quietly and simply, occasionally growing peppers and tomatoes in the garden out back. He loved purely, his blue eyes windows into the soul of a godly man. He helped build the nearby church, never missed a Mass while I was growing up, and yet I never heard him preach, judge, nor condemn a single person. I never heard him swear, nor lie, either.

He was an exceptional man from what feels like a bygone era, when decency, and good manners, were considered essential traits of all citizens. It’s hard to fathom the changes he saw in his ninety-eight years, but no matter what the fashions or trends, from the Flappers to the Hippies, from Disco to Heavy Metal, his brand of kindness never went out of style. It was never old-fashioned and neither was he – just the purest font of light, with a whistle for the birds and a smile for your troubles.

On Thursday, July 26, 2018, Francis Norman Saran, 98, passed away peacefully in his home, the one he built with his own hands. No palace of Versailles or manse for a Lord, it nevertheless sheltered generations of my family – his family – through stormy summers, hurricane season, and the bitter cold New England winters.

He will be remembered and missed.

_____________

Great stuff! Damn it’s misty in here. I miss my old man and my grandfathers.

Apologies to pep – I lol’ed when they made him a bazookaman too.

Thanks, Drake. He endured the indignity of humping that bazooka like he did everything else in life, (most especially being married to may grandmother), with a peaceful stoicism, punctuated by a puff of his pipe.

At Parris Island before a long march, our Drill Instructor innocently asked who was going to Radio School. Another recruit beat me to raising his hand – and was handed a PRC-77 which is about the size and weight of a cinderblock.

I have had the pleasure of humping the “Prick”-77, Drake. Believe it or not, they gave them to us as officers at OCS and TBS, just to make sure we didn’t miss out on that unique pleasure.

Holy shit, talk about miserable. What I like is how there is no comfortable way to carry it.

The hallmarks of a successful contract.

“Never forget that your weapon was made by the lowest bidder.”

– Murphy’s Laws of Combat

Me too. We had them in my guard unit before getting the sincgars. i think there was a radio board or adapter for the ruck frame, but easiest was just throw in the ruck in the inner radio pocket, and dump everything else out in the waterproof bag when dropping rucks.

Spent a lot of time in the poison oak infested woods of what used to be Camp Adair’s training area.

I somehow drew a PRC-105 for a mech once. The really heavy long-range beast. The thing still had vacuum tubes in case we got nuked. Damn near killed me. On the Air Team I usually had a 113 which was better in every way.

March, not mech unfortunately.

I was going to bring up the 105’s because we got those for a couple of exercises and that one was a pain in the ass, too.

I am so glad I was a pilot. I have mad respect for grunts because humping your life on your back is just… soul-sucking.

What did you fly?

I was on the Forward Air Control team. We loved Marine pilots because they think and flew like grunts. Navy was okay, Air Force to be avoided. Unfortunately saw an A-10 waste a Marine LAV with some of the crew during the Battle of Kafji. After that, they stopped tasking Air Force flights to support Marines which was good,

Cobras – Whiskey model. I was in an east coast skid squadron from 93-96.

Heh – As a Lance Corporal I once had to explain to an Infantry Company Commander that I couldn’t tell Cobras to hover over his position like flying tanks while he advanced his company. (There were ZSU-23/4s about, for one reason) Either give me a target or solve your own problems, sir.

+1 Flying Artillery

Army pilots used to mock us because of how we were employed doctrinally, but I really liked being in support of the grunts. There is no better mission and really, that’s what we’re best at. We can come in low, really see the FLOT, and make sure we’re shooting bad guys and not good guys.

I’m still stuck on an old fashioned view of just war. Close support aviation is what airpower should be about. Strategic bombing is very questionable. I know the arguments for total war, and I even agree up to a point, but bombing of civilian targets, especially in a war of ‘liberation’ is not right. This all gets boiled down to questions about the a bomb and Hiroshima/Nagasaki, but what we did to Tokyo and Dresden and Berlin was actually worse.

JarFlax – I’ve got several of Victor Davis Hanson’s books, but the ones about war seem to me to be extraordinarily good on this exact subject. The Prologue to “The Soul of Battle” might be the best thing I’ve ever read on the subject of war – and I do not say that lightly. It includes a stunning recital of Curtis LeMay’s influence on and conduct of WW2’s air campaign. I highly commend it to you on this subject.

False!

There is a perfectly comfortable way to carry one.

In the radio rack, in the back of your turret.

Armor, the Combat Arm of Decision!

It’s no King of Battle.

Artillery is just a transportation problem.

Getting explosive material to the right place at the right time.

It’s there for you to call an engineering vehicle to pull your platoon out of the mud again, isn’t it?

Relevant?

https://youtu.be/TCXwgPZXScM

Engineers do a great job getting their own vehicles stuck without our help.

And 1500 hp can make up for a lot of stupidity.

Also, the only thing that can pull a properly stuck M1 is multiple M1s or M88s.

The Engineers don’t have anything that can pull 70 ton.

Mom’s dad spent the war on top of a building in NYC with a Bofors 40mm waiting on the LuftWaffe.

His brother was blown up 24 Dec 1944. The body was returned in the early fifties.

Very sorry, Don.

Of that war I think it is particularly apt: “All gave some; some gave all.”

Well I’ve relocated to the Inland NW and boy has the new time zone interrupted my ability to ignore the lonks jump into the comments. I’ve not lurked for a week but this article from my news feed was too derpy to not share:

https://www.avclub.com/south-park-recognizes-the-need-for-nuance-without-actua-1839848663

*ignore the links and jump into the comments*……the new time zone has not affected my mad typing/proofreading skillz

This is my least favorite episode of the season. Actually, I’m really disappointed because I felt like the first 6 episodes the show really did a good job of making valid points with its off-color humor, but this episode was severely tone-deaf.

You’re not supposed to make fun of my sacred cows!

People are being marginalized!1!

Oh NOE, they gored my ox!

AV Club has a terminal case of woke. Take it out back and Old Yeller it.

And The Onion just can’t figure out why they’re being displaced by the Babylon Bee.

Beautiful, Ozy.

You honor the man. Thanks for sharing this.

Thanks, Tundra. Like most portraits, I’m not sure I’ve been able to fully capture his essence with my “brush,” but I felt compelled to write it. My father liked it and that probably was sufficient stamp of approval to allow me to publicize it without feeling guilty.

mad OT:

I’m looking at some product engineering work, mostly supplier quality footwork and a ton of travel. That’s a good fit, so generally no worries.

But I haven’t worked in Mexico in four years and had opted out after Guadalajara came apart on me in 2015. I had a latin partner on that trip, but when I have often worked alone there I’m super conspicuous: I’m super white, blue eyes, and a foot taller than half the folk at the airport.

I love travel, culture, and learning to cope with other languages, but I thought Mexico wasn’t my problem anymore. Anyone else have recent experience with sticking out like a turd in a punchbowl in abduction country?

Anyone else have recent experience with sticking out like a turd in a punchbowl in abduction country?

Ummm. Carry a bunch of Beer bottles around with you. Whenever someone looks threatening just smash it against your head and cut yourself with the left over shards while making a “I’m gonna kill you, and in a not very fun way” face.

I’ve been down to Mexico a handful of times in the last year and I didn’t feel threatened or have any problems. I was also traveling with a few other dudes, and some women, but it all felt pretty “normal.” I think it depends upon where you’re going and how you handle yourself. Situational awareness is key, as is knowing where & when you’re most vulnerable – and then ameliorating those situations as much as possible. FWIW, most kidnappings occur getting into or out of a car.

Ozzy, This looks really good. I’ll have to read while i’m at the doctors waiting room when i’ve got more time.

Great write up. Thanks.

Your author voice is lovely.

OT

Go back to California

Thank you, Mojeaux! I’ve never been called ‘lovely’ in any context before, so I’m kinda psyched.

/starts whistling while making oatmeal

“I took the position that I would come to Idaho and adapt to the community,”

At the college interview, “I was dressed professionally, looked like a Californian,” Flanigan said. “I probably irritated [the director] by my confidence. There was no way she was going to have me volunteer…. She wanted to get rid of me.”

Everyone knows them dumb Idahoans don’t dress nun good. I shoulda come in with overalls and a blade of grass in my mouth.

I wonder what the de facto “minimum wage” really is. If it’s so damn expensive there now, it ain’t $7.25.

It’s not that they are from California, it’s that many of them bring that “holier than thou” California attitude with them.

And California mores and California voting habits and California traffic.

They bring shit tons of cash and price the natives out of the market.

Yep. The house we bought is a house the natives wouldn’t have bought.

That was a great Tale Ozy, thanks for taking the time to write it up for us all.

My grandpa is 95? He was 17 in the Navy at Pearl Harbor, his ship died of fright, it shook itself apart from the shockwaves,

Thank you, Yusef.

Also, I know I owe you a phone call. I’ll ring you up in a little bit. I forgot I couldn’t call after I landed because I didn’t have my phone with me when I traveled. And it’s been 48 hours of a struggle trying to get back on US time, so my apologies.

No worries,

Two things:

1. This is a world-class piece of writing. I have been a magazine editor for almost 30 years and if I worked at a consumer publication I would buy this instantly and not change a word.

2. I hope your grandkids look at you the same way when you are old.

1. *Blushes* Thank you. I offered it up here because I know there are “real” writers and editors and the like and I was hoping to get some feedback on it. I think it is one of the better things I’ve written.

2. I dearly hope they do, too. The difference is he was a bona fide saint; and I’m… not… him. Not yet, anyway.

But it’s a great blessing to have someone like that in front of you as a model.

OH! Shame on me for not saying this sooner, but thanks to our own Tonio who took me up on my offer and edited this piece before it was published. It really helped clean this up.

I managed to find one or two errors, but those are entirely of the “it’s a word, but not what should be there.” Like I found an “out” where I think it was supposed to be “put” and a “may” where it should be “my” – but those are on me.

Thank you, Tonio!!

You are most welcome. Thank you for trusting me to edit this. It was a pleasure and honor.

And for the record I mostly just added more whitespace and spelled out numbers he had written in numerals. I didn’t do any rewrites; it’s all Ozy.

What a great read! Thanks – and now I miss my grandparents too.

My father’s father passed when I was 17 (was was born in the early 1890s — for real). So I never got to know him that well.

Being of Irish descent, he was an amazing story teller. He spent nearly half an hour explaining the circumstances that led up to and followed a bus crossing the center line on the street and ripping off the rear fender of his model T. When it happened, he didn’t stop, didn’t slow down, and never looked back.

My father, now 83, inherited the gift of gab from his father, but it somehow passed me over.

I think you’re doing just fine, Kinnath, for whatever that’s worth. I always enjoy reading what you post. Consider that some of us who are more long-winded wish we had your ability for concision.

/Low fives on the way by

Up high, down low, fuck I never get this right

thanks

Up high, down low, fuck

Well, that escalated quickly.

These euphemisms!

This was excellent.

Thanks, Jar. Due entirely to the person I was profiling. He was one of a kind.

A buddy of mine from high school had a crazy old grandpa who was a WWII Marine. We used to do Revolutionary War reenactments (he owned a for real cannon). Around a campfire we would try to get him going with war stories. He was on the Wasp when it sunk and hit the beach at Iwo Jima, so he had some real dozies.

I feel so blessed that when I was at BU, we had a LOT of veterans around. After I married into South Boston, I lived right near the local VFW post in City Point, which was just a room with a bar where the old salts would hang and drink. They loved having some new boot lieutenant to haze and tell stories to, and so I got to hear (for example) from a guy who was one of Chesty Puller’s runners in Korea (at Choisin, no bullshit). He had lost most of the toes on his foot, so the boys got him sandals as a birthday gag gift. The AD at BU at the time was also a WW2 Marine from Bougainville, Tinian, and Saipan, I think. Holy shit, did he have some stories. My grandfather may not have wanted to talk about it, but I heard plenty from veteran Marines who knew that part of how the tradition gets passed is by sitting around and talking about the good, the bad, and the ugly of war. I’m eternally grateful for those men (and women! I’ve even met some WACs and other women who did unreal stuff to support the war effort).

South Boston? 30 years ago this month (how fucked up is that?) I transferred from the Regimental HQ into H&S Company, 1st Battalion, 25th Marines as they were deploying to Desert Shield. Back then they were based at Camp Edwards on Cape Cod and probably half the company was Southie Irish guys. (I think they were moved out to Fort Devens since). I probably know some of those bullshitters you met.

After we got home it was very cool to watch our battle streamer pinned to the flag next to ones from Saipan and Iwo Jima.

I’m certain we know some of the same bullshitters. I know a lot of folks at 1/25 and used to know a bunch of the leadership there. I think the HQ is now in Worcester.

Wasp

Dad had an aunt who was a WAVE. She married and moved to MA after the war, so he only saw her twice again and I never did. She just died last week, 95 I think.

Got a little dusty in here.

Great story, Oz.

Ditto.

Awesome work Ozy. Your story reminds me of my grandfather on my mother’s side. WW2 vet of the Army and Navy. He was a radio operator. I grew up in the opposite coast but my memories of him are an easy going, whistling man that never got angry or mad. Except one time when my sister and I were fighting. We stopped immediately when he raised his voice.

My grandfather on my father’s side died when I was young. My dad doesn’t talk much about his father. I might ask him about it when I see him over Thanksgiving.

Thanks, IB. And ask your dad about him, if I can be so bold. He’ll appreciate it.

Oh I left out, not just your voice but your pacing is excellent.

Reports: Numerous Persons Shot at California High School

UPDATE: Los Angeles County Sheriff reports suspect is in custody.

NBC Los Angeles reports “at least six people were shot” but there is no information on their condition.

KTLA reported that deputies “responded after receiving a gunshot wound call just before 7:40 a.m..” The noted “at least three victims” were seen being treated.

It’s gonna be hard for the grabbers to froth over that one. Although I guess they don’t need much.

I wonder why they don’t talk about Chicago…

It’s gonna be hard for the grabbers to froth over that one.

When has that ever stopped them? Was a firearm used? Yes/No? Then moar gun control harder! That is their objective. Stopping gun violence, whatever that is, isn’t it.

B-b-b-but… unpossible! Ce n’est pas vrai! Everyone knows that California passed sensible gun control and it prevented exactly these kinds of things from happening!

/progderp

amongoose You Guessed It • 10 minutes ago • edited

I think my guns might be Democrats. They lay around all day long stay loaded, don’t work, and expect me take care of them.

More info.

To many questions were being asked about Epsteins death again….

:Adjusts Tinfoil Hat:

Not sure why, but this bugs me.

Because it ain’t the business of the federal government.

Over-bearing supervisor in chief

Well done sir. Top notch writing that quickly pulled me in to your relationship with your Pepe. You provided a great portrait of a good man and good father. It got a bit misty for me remembering my own father and grandpas as well.

The depression era folks like your Pepe and my Grandmother have attitudes I strive to emulate.

Thanks, TL. And yes, I feel more of a kinship to the Depression Era folks than I do to the Boomers, though my parents are wonderful exceptions (in the important ways, I think) to their generation.

Ozy, I know that your granddad and dad are proud of the son they have, as you can be proud of them. I like your style of writing, keeping us in the middle. I spent a bit of time in Europe and am a little familiar with the Verdun area and around Kaiserslautern.

I wish WW1 would have been the last war but unfortunately as we are well aware humans are always covetous. In today’s world of instant communications one would think there would be no need for these conflicts. Politicians always seem to be generous with someone else’s money and kids.

Thanks for a great article. As others have said, a mite misty.

The memories of VN that my brothers and I told each other mostly dwelt with the comical things that always seem to happen, young men being young men.

Politicians always seem to be generous with someone else’s money and kids.

This times about a bagilion. We’ve given them too much of both.

+2 bagillion

Took me a while to get through. Great writing Ozy. I love the juxtaposition.

Ozy, great story. I promised you a critical review, and I’ll provide one in a bit. But I’m not seeing a lot to comment on.

Thanks, Leap. No rush.

That was a great read, Ozy. Thanks for sharing it.

Another fucking school shooting? Really? WTF?

It is raining all day today so I had a couple of shots and slept in. I wake up and Mrs. Suthenboy has her TV shows on. She watched two re-runs of In The Heat Of The Night and then switches over to the news.

16 YO Asian male, 45 caliber pistol shoots up a school in California, land of gun control. Six shot, two dead. Fuck. Just Fuck. The gun grabbing lying sacks of shit are gonna get cranked up again.

land of gun control

It is well known, that Hosiers have set up many gun stores in Nevada, thwarting all their laws. This is why we need national gun control.

And is so incompetent he can’t suicide correctly using a .45 to the head.

Who is gonna shoot up a school full of children??? Only the craziest of the crazy and evilest of the evil would even consider something like that so incompetence is not surprising.

I apologize Ozy. I haven’t had a chance to read yet. I have to take the wife to girl’s night out in a bit and while she is in the restaurant Jack (giant catahoula cur) and I will read and comment. Reading what you have written before has been a good investment of my time and I am sure this will be no different.

No apologies necessary, Suthen. I’ll check back for your comments.

I’m very grateful that I had the chance to read this carefully and absorb it.

Thank you for taking the time. I echo the comments of others above: it’s not just the subject matter, which is inherently fascinating, but the manner in which you presented the tales.

Thank you.

Thank you, HighEx! It’s gratifying to have such an audience. Many thanks to TPTB.

Dad, six uncles and one aunt put on Army uniforms for WWII. Uncle Richard didn’t return. All are gone now but they marched where duty called.

The phony opioid crisis is once more being used as cover for more bureaucratic empire building. Where’s my shocked face?

https://www.oregonlive.com/news/2019/11/lax-tracking-of-veterinary-drugs-in-oregon-draws-scathing-rebuke-from-state-auditors.html

My favorite (and I mean that in the opposite sense) part of the opioid crisis is that the US government controls the amount produced annually. IOW, it’s a “controlled substance.” Controlled by whom? The government, that’s whom.

They determine the amount that these companies can make – you can find the exact number in the federal register or somewhere – but the USG has the levers on exactly how much gets made. Now I’m certain the bureaucrats would instantly point the finger at industry, but the legally operative fact is that the govt sets that number on an annual basis. So, maybe, just maybe, that should be lower than the number they set it at, if we’re to take them at their word.

Of course, no one ever brings this up.

I think the crisis commingles several issues of which illicit imports from China are a grave concern. Further, those imports are used to cut/spice up other drugs (I don’t know these details, sorry) because the stuff has such a fabulous power/$ factor. So a heroin addict who gets a spiced batch and ODs goes on the national report without regard to whether he even wanted to do opioids.

-1 Black Markets

Addicts know they’re playing with fire. When they get burned by it, that’s one of the very few things the don’t whine about.

Ozzy, Fantastic work. I’m always impressed with the caliber of writers we have on here. Yours is always very, very good, and the Subject matter is never dull. Thank you for contributing.

Thanks, Leon. Glad you liked it.

My phone won’t let me reply, except to respond.

Anyways, great post. I can only read in pieces because I’m at work, but man it’s an impressive bit of tale telling. I can only hope to one day be a tenth as good at writing. My hat is off to both you and your kin folk. Thank you sir.

blackjack – I really enjoyed your story, as well, and would love to read more of your writing. You write quite well and a copyeditor cleans up a lot of the “overspray” and other mistakes.

Quite impressive, Ozy.

It has already been mentioned, yet I want to add my appreciation of your use of juxtaposition, which I find well balanced and appropriately meaningful at each instance.

At one point I wondered how long the piece was going to be and at that very same moment I continued reading. I was drawn in, if you will, and for many good reasons. I do not think that this work should be any shorter: You have to use the proper amount of words to convey who this man was at the very core of his being and what he meant to you and his family, and what he and his contemporaries meant to their fellow soldiers and their nation.

Now that you have presented this, Ozy, you should always remain cognizant of the fact that your grandfather will continue to live in my memory, and likely in the memories of everyone who reads your work. “Long live the King”, indeed.

Well done, Sir.

Thank you, Mr. Easterly, you do me a great honor. In a more venial bent, I can’t help but think I’ve given away the game. Now that I’ve put this up here, the next time I’m an asshole in the comments, you’ll all have this to remind me of.

And yes, it was meant as a tribute in the small way that I can to someone who was immensely important in my life and I’m not sure I ever properly conveyed to him.

“… I’m not sure I ever properly conveyed to him.”

Of these burdens, Sir, you are not alone.

I recall many statements from individuals whom I have met during my life (or read in their correspondence or comments online, et cetera) that have expressed similar regrets.

Here again I think that your tribute might yield results beyond your original intention.

How many who read this (either here or in some future publication/format) will presently or in the future realize that they will regret not having said or done something meaningful for an individual they appreciate?

Additionally, you detailed your suggestion to your grandfather to watch the movie “Saving Private Ryan” with you, and you seem to have regretted ever having made the suggestion: “… I regret asking that question to this day.”

Yet again you have given advice, in my opinion, albeit of another sort.

Perhaps readers can benefit from your own experience, and attempt to not make the same “mistakes” you think to have made.

Charles

Thank you, Charles. That’s exceedingly kind of you. I’m probably being overly hard on myself in that piece. Or I was when I wrote it. I see it for what it is now, me trying to reach across a two-generational divide to connect with him, but that was the wrong thing. Sports, our teams, were places where we could bridge that cultural-generational gap. The military/war was the wrong thing to reach with. I wish I hadn’t done that because that was for me and not him, but it’s less grave an offense than I painted it.

Incredible story, Ozzy. Thank you for sharing. Your writing brings it to life.

It’s impossible not to think back to own grandfather while reading. I have a collection of letters he and my grandmother wrote to each other as he volunteered for WWII and was shipped off. I don’t really know why but it means a lot to have and read through

This came out of me getting his WW2 yearbook given to me by my father. It was in rough shape, so I spent a decent penny at a place that does historical preservation of documents to get it rebound and better preserved. Amazingly, the unit’s yearbook (at least most of it) is available online along with a number of others. It seems to be historically significant in that the commander had all of the field reports, as well as some maps and other documents, bound and published, and then one given to each man in the unit.

Our Guard brigade’s predecessor NG division published a division history shortly after WWII. I found out about it long after I got out, along with the division association (sadly dwindling). Of the greatest shames to me is that the history, available as print on demand, wasn’t distributed to every one entering the brigade and that the Association wasn’t integrated with the modern brigade the way active duty division associations are.

One of my to do items is to visit the division chapel in Australia.

Wow, what an awesome read!

I’m glad you liked it!

I’ve *got* to go through my grandfather’s records. I got the entire hard copy from the National Archives (courtesy of my aunt) – Enlisted WWII, Warrant, OCS, Korea, Vietnam….haven’t set aside the time yet, but this is really motivating.

Never really talked to him about any of it (far too young at the time).

Thanks Ozy

BTW, when I went to school in Malaysia, we’d make “doughboys” camping sometimes – wrap the dough around the end of a stick, brown it in a campfire or clay firepot, and then pour golden syrup into the middle. Good times.

My youngest daughter read this piece and vowed that we would make them when she comes for Thanksgiving. I used to make them when they were young. So, the tradition lives on.

Fine writing, Ozy. you brought your grandfather alive for us.

Thanks you, myb.

That was a very good read and tribute to your Grandfather Ozymandias. He resembles my Grandpa, who I revere, in many respects. My Grandpa was second wave at Utah Beach on D-Day and took shrapnel to the chest from a mortar crossing a stream on the 7th day. He had been fighting for 3 days straight with no sleep when he got hit. The sniper fire in the hegderows was so heavy that no medics could help him. He eventually crawled to a first aid station hours later. The next thing he remembers is waking up on a medical ship 3 days later.

After several months recovery, he was redeployed in an ADSEC unit just behind the front lines in Patton’s 3rd Army. Outside of funny stories, this is all the info he ever told any family members regarding the war. He never told me any of this until he was in his 80’s. After the war, he just wanted a simple life and to tell jokes. He rarely traveled far from his small farm surrounded by woods in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. If you read this Ozymandias, I believe there is a mistake in your article in that it was Patton’s 3rd Army and not the 8th Army that did the maneuver to Bastogne.

Pud – I did read this. You are correct – it was Patton’s 3rd Army, not the 8th Army. Thank you for that.

And thank you for sharing your grandfather’s story; I suspected when I first wrote this piece that there would be a lot of people who would be able to identify my grandfather with someone in their family. I don’t think he was unique among that generation, both in his service and in how he handled it coming home. They really were “The Greatest Generation” regardless of what else they may have gotten wrong in public policy from our libertarian perspective. They went willingly en masse into the German and Japanese killing machines, saw slaughter unlike anything the world had ever cooked up, then came home, didn’t talk about it, and went about raising families and rebuilding their lives.

Thank you again.

Ozy, this is a great read. Your grandfather sounds like a great guy.