I have zero guilt about pointing out how awful compulsory public education is. Now, when I say awful, I don’t just mean bad like everyone else who’s lamenting the woes of publicly funded education in the aftermath of U.S. test scores being released; I mean it as a matter of morals. Forced state education isn’t just another item in a mind-numbingly long list of overfunded, underdelivering government institutions that swallow vast sums of taxpayer dollars while completely ignoring its original charter… like Congress or the Supreme Court, for example. No, compulsory public education is worse because it is an indoctrination center for our children’s minds, an obedience machine, that feeds and fuels the rest of the items on the above list of bad government, irrespective of whether it’s my list, or your list, or your neighbor’s list.

If anyone truly wants to fix what’s ailing America and make it a livable bastion of freedom into the future, it won’t matter what other arguments you make in the public square or what legislation We, the People, get our bought-and-paid-for politicians to finally push through to tinker with some other broken institution. None of that will matter one whit; it will be only a temporary band-aid on the sucking chest wound of the body politic until we destroy compulsory public education.

I know what you’re thinking: Don’t sugarcoat it, Dale; tell us what you really think.

I love learning; always have. I consider myself a perpetual student and tell friends and loved ones that the day I stop learning will be the day you all are kicking dirt over me. But that love of learning is exactly why I hate public education as it currently is constituted. When I graduated from Boston University in 1991, I told everyone I knew: “I swear to God I will never go to school again. I’m done.” Sixteen years of the U.S. education system had ruined my love for not just education, but learning itself.

Paul Lockhart’s brilliant essay-turned-book, “A Mathematician’s Lament,” explains how public education destroyed his favorite subject, mathematics, but it applies with equal force to all subjects. Indeed, one might well observe that Lockhart’s Lament is simply a slight-variant of the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect, in which a person reads the front page of the newspaper, noting to herself how completely wrong it is, only to turn the page and treat every subsequent story with complete credulity, as if they were somehow of a different specie. I don’t want to impute opinions to Lockhart that he doesn’t hold, but his introduction strongly implies that he recognizes public education hasn’t only ruined mathematics.

A musician wakes from a terrible nightmare. In his dream he finds himself in a society where music education has been made mandatory. “We are helping our students become more competitive in an increasingly sound-filled world.” Educators, school systems, and the state are put in charge of this vital project. Studies are commissioned, committees are formed, and decisions are made – all without the advice or participation of the single working musician or composer.[1]

Lockhart fleshes out this nightmare in the succeeding pages in satire worthy of Swift, finishing the scene with the devastating postlude: “Meanwhile, on the other side of town, a painter has just awakened from a similar nightmare…”[2] The critique repeats itself for that subject and it doesn’t take a genius to recognize that the same issues raised in the musician’s and painter’s nightmare apply with equal vigor to all subjects.[3]

I had a great personal experience with the Gell-Mann amnesia effect before I had even heard of the term. Over breakfast one day, I asked an older business associate about a long-form article I had read the day before; it concerned a subject that I knew he had extensive knowledge and experience with.

“What did you think of that story?” I asked, quoting the source.

“It was garbage – complete and total shit,” he said over bites of his breakfast burrito. I raised my eyebrows in response.

“Really?”

“I only know one subject really well and that author has no idea what he’s talking about.” I made an “Ahhh” face and dug into my breakfast.

“Let me ask you something,” he went on after a brief pause, “You ever read a newspaper or magazine article about a subject you know really well… like flying helicopters, for example?”

I thought for a moment.

“Sure.”

“Well? Were they ever any good? Did they accurately portray what flying helicopters was like?” I gave it some thought.

“Nah. Not even close,” I replied. Probably 90% of the stories I’d ever read that were about just being in the military fell into that category, as well.

“Then why do you assume that it’s only the subject that you know about that’s like that and not anyone else’s…?”

I sat there with my mouth open for several moments while that sunk in and changed my entire worldview on the press.

As Fate would have it, when I matriculated from BU with half an English degree and half an Engineering degree (and not in that order), notwithstanding my proclamation that I was done with formal education, I knew I was headed right back into another “education” pipeline as a newly commissioned Second Lieutenant of Marines. Like all new Marine lieutenants, I would spend the next 26 weeks learning how to be a basic infantry platoon commander and Marine officer at the aptly named “Basic School.” The acronym TBS (include “The” at the front) would get all kinds of wonderful student monikers, such as “Ticks, Bugs, and Snakes,” or “Time Between Saturdays,” a fair description of the general Monday thru Friday routine, with Sunday largely devoted to getting uniforms ready and prepping for the upcoming week’s field exercises, live fires, or patrolling, or – worst of all – hours spent sitting in the classroom getting lectured on everything from military administration (Marine Corps-style) to the German war machine’s blitzkrieg campaign to military customs and courtesies to how to write a fitness report, thus earning it my favorite nickname, “Thousands of Boring Slides.” Yet as bad as it was at “The Baby School” – and whatever justified criticisms can be leveled at military training and education – it was a considerable upgrade from what I had endured in the prior sixteen years.

First, I note that TBS had training, a necessary sanity-check and counterpoint to classroom education. There may be some merit to sitting in a classroom being force-fed hours of lectures, slides, and discussions about any subject, but those benefits are shadows compared to the benefits of hands-on training, particularly when the subjects are closely related.

As an example, when I went on to flight school, i.e. Naval Aviation Flight Training at NAS Pensacola, Florida, our first six weeks consisted of something called AI, Aviation Indoctrination. The best cultural reference I can call upon is “An Officer and a Gentleman,” except that all of us were already officers and had gone through Officers Candidate School, so we didn’t have Lou Gosset breaking our balls.[4] The altitude chamber and dunkers, swimming tests and obstacle courses, the boxing and academics, and all of that other fun stuff, however, was fairly well-depicted.

What they don’t show in the movie is the genuine interest our instructors had in wanting the students to learn the material. They viewed and treated us as fellow professionals who might be in the air with them someday, a not-too-ridiculous possibility. Most of our instructors were just there as a temporary duty away from the cockpit after a successful tour as a pilot. So, there is Huge Difference Number One between real education and academe. Universities and even high schools have raised ‘academic freedom’ to a deity-like status; tenure for professors is supposed to inure them from bureaucratic concerns, yet nothing could be further from the truth. Most academics have not even a nodding acquaintance with the practical application of whatever subject they’re teaching, as Lockhart notes – and this is, in my experience, even more prevalent, worse in every way, the higher one goes up the education ladder. Take a look at how many economics or MBA professors have a track record of successful business endeavors. How many are heading back out to ‘the real world’ after just 3 or 4 years of teaching? This also makes a huge difference in the relationship between teacher and student.

Our course on jet engines wasn’t only tons of pages of reading from a book and hours of lectures – although there were plenty of both of those. We also had two jet engines in our classroom, cutaways that you could rotate, and see the various sections and how they worked together: the intakes, combustion chamber, the stator vanes, compressor, the accessory gear box and where other components attached, the splined shaft that ran the length of the engine, etc. One of the engines was a very close cousin to the one that would be powering our training aircraft, the T-34C Turbo Mentor. Thus, we had not merely dry recitation of theory, but also hands-on experience with a no-kidding jet engine that we would see in a month bolted inside of our aircraft’s engine compartment.

One can, of course, point to a myriad of other factors that differentiate military training and education from “regular” everyday education of the citizenry, not the least of which is the ‘death’ factor. Military training at its core is about killing other people, who will likely be trying to avoid that fate and also to inflict it upon you; that has a tendency to sharpen the mind in ways little else can. The differences in education needs, however, are not as significant as one would imagine. First, there are many professions that are significantly more dangerous to life and limb on a daily basis than the military – (and no, the police isn’t one of them. Not even close. Firefighting usually doesn’t crack the top 30 either). Tree work almost always ranks among the deadliest professions on the planet. Underwater welding is also no picnic and the margins for error are razor thin, yet none of the aforementioned careers relies upon the model that we as a nation are currently inflicting upon our children to train and educate them for their future. Second, having put four daughters through a variety of education systems, from DoD schools, to very highly rated school systems in Boston suburbs, my takeaway from it was that they truly are about indoctrination, and in some cases, it’s not even subtle. To wit: when the last President was running for his second term, I had three daughters in high school together. ALL of them were mandated to read a sitting President’s autobiography and write a paper about it; the oldest would be eligible to vote in the upcoming election. Worst of all, the youngest wrote a paper critical of the autobiography, and got her worst grade in all of high school because of it. The other two were smart enough to regurgitate what their teachers had already made clear in class – and they were graded accordingly. I read all of the papers

Training and Education together are wonderful complements, facilitating learning, yet it strikes me now that the only training there ever was in public education took place in the arts: whether it was Music, Language, Art, or Gym class. (I purposely eschew the term ‘physical education’ for ‘gym’ because it is another one of those wonderful, modern malapropisms that is helping systematically destroy the English language). Vocational training has all but disappeared from high school and middle school. I know this because I’m old enough to have been in school when public education shifted from its Prussian roots of identifying who the laborers would be and who was destined for college – and therefore middle management – and schools instead became college-entrance mills, a pipeline for everyone, regardless of aptitude or even desire, to go to almighty college. By the time I was in high school in the mid-80’s, society had almost gotten to the point where we are now – where anyone who didn’t want to go to college was considered somehow a less than. Despite my best efforts, my four daughters cannot help but believe that anyone who does not go to college will shortly become part of the homeless population.

Ohmygod, you’re not going to college?! What will you do?? How will you even get a job?!

It is likely not surprising to anyone with a little history, or experience in that part of the world, that the Germans first established the public funding of compulsory education.

Utilization of the property tax to support public schools is an Anglo-Saxon tradition, in the history of the tax is inseparable from the movement for universal, compulsory, and free education that arose from the Reformation and constituted one of its greatest influences on Western culture. There was a nascent belief among the Protestant peoples, particularly in Germany and England, that universal education was necessary to ensure the welfare of the “state” in a period of rising secular nationalism, to assure that individuals could read and interpret scripture for themselves under the Protestant religious systems, and to ameliorate ecclesiastical and monastic control of education previously exercised by the Catholic Church.[5]

This experiment and tradition managed to transmit itself across the channel to the English, and also over the Atlantic Ocean to the early New England colonies. The Puritans in the Massachusetts Bay Colony passed the first compulsory education law in 1647. It called for every town of 50 families or more to have a schoolmaster and every town of 100 or more families to have someone who could teach Latin and prepare students for Harvard College, which had been established in 1636. (Just for perspective, consider that two years later the first printing press in the colonies was established at Harvard.)

The intent of the Act of 1647, called the “Old Deluder Satan Law,” was to ensure that every child could read the bible and knew the central tenets of their Puritan faith. The law got very little traction outside of New England, although the district system it established with local control over the curriculum would eventually come to be the model for the Nation – several hundred years later. It’s also worth noting that 45 years after the law was passed the Salem Witch trials took place in Massachusetts. So much for the merits of education abolishing ignorance!

But Dale, there’s proof right there that compulsory education has been a part of the Republic since the very beginning!

True enough – all manner of slavery was extant in the early colonies, but that’s no justification for its continued existence. It’s a naked appeal to tradition as authority. An interesting historical fact often overlooked by scholars to me, however, is that the early colonists established various legal regimes, done so under their authority as British Crown subjects, that continued ‘on the books’ as it were, even after the Declaration of Independence and Constitution had undercut or outlawed the foundational principles upon which these legal regimes rested. (‘Sovereign immunity’ is a good example of this).

In the case of compulsory education, the colonial law of Massachusetts rested upon notions of authority that emanated from the Crown, as the Divine Head of State, with his/her authority coming directly from God. The most radical notion in the Declaration of Independence was not that a group of subjects rebelled and declared their independence from a monarch – that had been happening for as long as there had been monarchs, both on the Continent and elsewhere – nor was it that “all men are created equal” and imbued with “unalienable rights.” Such notions had justification in the Bible and other significant religious and political movements prior to the Founding Fathers. No, the most radical political notion in the Declaration of Independence was that “Governments… deriv[e] their just powers from the consent of the governed” and furthermore, that ‘the governed’ could “alter or abolish” these forms of governance whenever it suited them to do so.

Compare that sentiment to the notion in the Old Deluder Satan Act that ‘the State’ could compel the citizenry of every town to (1) appoint someone to educate their children, and (2) pay for it out of their own pockets. And if one still insists that there is no conflict, or that the people of Massachusetts ‘consented’ to such a form of governance, that argument falls apart when run up against the First Amendment’s anti-Establishment clause 140 years later. Early colonial schools were not beacons of secular Enlightenment thinking, teaching scientific ‘truths,’ or other anti-religious curricula – they were explicitly religious indoctrination centers designed to ensure the continuation of the Puritan strain of religious thought.

Lest this seem like a mere academic argument in political theory, it’s worth noting that John Hathorne, the chief inquisitor during the Salem Witch Trials, was born in 1641. He would have been 6 years old when the aforementioned Law was passed. While I cannot find direct evidence of his attending the schools so established, there is significant circumstantial evidence of his having received an education under that system, given the prominence of his family in Salem and surrounding Essex County, and biographical evidence of his start as a bookkeeper, later land speculator, and then his having served as a significant political and judicial figure in Salem, Mass., and Essex County.

Oh, c’mon Dale, you’re using an extreme example, a strawman of what modern education really is to justify your hostility to it. You’re not seriously suggesting modern education is equivalent to the Puritan education model.

“Modern” education certainly didn’t begin with the Puritans, although the vast majority of states that eventually created their own compulsory education did so based upon the original Massachusetts Act of 1647, or upon land grants similar to the “Land Ordinance of 1785” by the federal government that established Ohio into 640 acre parcels, with a set aside for schools. Widespread adoption, however, of compulsory state education had to overcome a number of hurdles, chief among them being the unwillingness of the poor (and most everyone else) to pay the taxes necessary to fund the system. Again, it’s worth remembering that the early colonists were people who resorted to acts of war over a 2 pence tax on their tea, even though it actually lowered the price of British tea in the colonies from what it had been. That tax – the Townsend duty – was a subsidy to prop up the failing British East India Company, an early example of the kind of political cronyism that is rampant and openly accepted today. Back then, however, the colonists went to war with the greatest Land and Naval Force history had ever seen over the principle of “taxation without representation” and the British abuses of what they saw as their God-given rights.

The other reason that compulsory education was ‘on the books’ but largely ignored (until 1852 when Massachusetts passed the first mandatory state education law) was that most people lived in rural areas. Outside of the few ‘big cities’ of the day, most people lived on a farm where parents were the major source of education, and which consisted principally of the skills necessary for daily living: farming, hunting, and/or whatever trade a person’s father practiced to make ends meet. Finally, there was – and continues to be – the common agreement that education itself is a “good thing.” The average person would be hard-pressed to argue against education, much less to make the distinction between private education and publicly-funded education and to argue the merits of either. Thus, there was no public outcry in 1779 when Thomas Jefferson proposed a “two-track” educational system for “the laboring and the learned.” Indeed, that Prussian model held sway until late in my childhood. Jefferson received no clapback, nor did he get ratioed on Twitter, for observing that the education system for laborers might “rake… a few geniuses from the rubbish.”[6]

Given these realities, one has to wonder what it took to finally see widespread adoption of the Massachusetts Model: much like every other plank in the platform of Progressivism, it was spurred on by good old-fashioned racism and fear-mongering, of the exact same kind that animated state education in the first place. The attempt by the Puritans to ensure their ‘posterity’ against the Catholic church was adopted by the broader Protestant population of the United States after waves of Irish Catholic immigration in the 1840s. Over a million Irish immigrants came to the United States fleeing the Potato Famine in their homeland. In the decade from 1846 to 1856, roughly 3 million immigrants arrived in the New World. That number represented about 1/8th of the entire U.S. population – and those Catholic immigrants didn’t want their children being taught Protestant theocracy. Private Catholic schools began to pop up in larger numbers via private endowments and other funding mechanisms. The Industrial Revolution also put large numbers of people in cities and factory owners needed compliant workers. It is no coincidence that Horace Mann, considered by many to be the leading figure in the history of compulsory “free” education, when he was appointed head of the Massachusetts State Board of Education in 1837, had offers to supplement his meager state salary from the pocket of industrialist Edmund Dwight, among others.

The justification used in the 1840’s and thereafter in favor of compulsory education was the ubiquitous “for the children.” Specifically, “assimilation” of immigrant children. The New York streets were beset by gangs of kids who spent much of their free time in mischief and crime. Nor was it a happenstance that the Ku Klux Klan was a vocal supporter of compulsory state education acts into the 1920s that would ensure the “papists” would not change the character of the Nation. Lest this seem like character assassination by lumping in the KKK with education reformers, they were following in a tradition that included people like Thomas

Jefferson, who was also an ardent supporter of public education for the same reasons:

Preach, my dear Sir, a crusade against ignorance; establish and improve the law for educating the common people. Let our countrymen know that the people alone can protect us against these evils, and that the tax which will be paid for this purpose is not more than the thousandth part of what will be paid to kings, priests and nobles who will rise up among us if we leave the people in ignorance.

Jefferson wrote the above to George Wythe in 1786, a legal mentor and friend, while Jefferson was in Paris, commenting repeatedly on the problems he saw with the influence of the Catholic Church in education in France.[7] Indeed, Protestant anti-Catholic animus remains a staple in American public discourse, from John F. Kennedy’s run for the presidency in the late 1950’s to Congressional hearings over Supreme Court nominations as recently as last year.

Okay, Dale. Fine. Regardless of your historical point, you’re not seriously arguing that we should end free public education. Where will kids go during the day? What will happen to poor children who can’t afford education? What will they do all day?

Some will claim that I’m belittling the best of the arguments for compulsory public education, but the above questions are a fair summation of what I usually get in response to my occasional rants on public education to those who will stand still long enough to listen. It’s also not an unfair summation of all of the arguments offered in favor of compulsory education over the history of our Republic. I want to give them their due, but because there are so many implicit assumptions that underlie these questions, I’ll ask for a little indulgence and “back into” my answer and proposed solutions. In an attempt to give air to these concerns, however, I’ll note that the ‘horrible hypothetical’[8] of gangs of indigent kids running amok on the streets if they’re not in school is not without validity. As I noted above, it was one of the factors that helped make forced primary education in the U.S. a reality in the first place.

I’ll also add two anecdotes to that sentiment: first, my friends and I grew up on the streets of Providence, Rhode Island. I attended Oliver Hazard Perry Middle School on Hartford Avenue, right across the street from the Hartford Projects, the same school my mother attended when she was a child living in those same housing projects. We – meaning me and my knucklehead friends – were just one of many gangs of (mostly, latchkey) kids roaming the surrounding streets and neighborhoods causing mayhem, much like the guy on the All State commercials, as soon as school let out. Second, a well-traveled business friend of mine once observed that his standard for judging the likely criminality of a society, or even a particular section of it, was by how many young men he would see standing around on corners or walking the streets with nothing to do. Reams of studies bear this out, however uncomfortable that may be for the male of the species.

Now, before I return to answer this concern and others, let me begin with the most devastating takedown of the public education system of which I’m aware.

Data. Placed onto graphs.

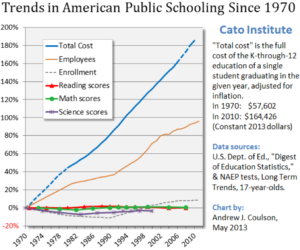

The late Andrew Coulson of the CATO Institute did yeoman work on the subject of education and its costs, along with numerous papers and studies over decades of research. It really doesn’t matter how the numbers are graphed, however, what domain or range is used, whether they’re placed on the abscissa or ordinate line, because the underlying data is all the same: the costs of compulsory state education almost always go in one direction – up – and the product that is supposed to result, student test scores, or literacy rates, no matter how they are controlled or measured, always stay flat, or worse yet, go down. It doesn’t matter if it’s per pupil spending, or by percentage from a zero line (such as the start of the Department of Education), total dollars spent (hundreds of billions), if it’s fixed to 2009 inflation dollars, or 2013, or 1975, on and on and on. The data only shows one thing: no matter how much this country spends on education, the results show little to no impact.

None of this data tells the complete story, either.

Consider that the DoE isn’t judged by some independent body, like the American National Standards Institute, for example, or audited by an outside agency. In fact, the DoE actually gets to determine what the standards are by which it will be judged, what the curriculum will be, and it administers the tests through its agents (the public school system and administrators). Notwithstanding all of this, it still fails. It’s like a student being able to write the questions for his own test and then complaining its unfair when he can’t answer his own questions. Only in the government, however, could one fail so miserably after spending tens of billions of dollars, and then with an absolutely straight face, look into a camera and say, “We need more money.”

It’s not enough to show that test scores and literacy rates haven’t improved, though. Nor to show the depressing amount of money spent with flat achievement lines. That’s just the tip of the iceberg. The real tragedy is that none of the benefits that the most ardent compulsory education advocates told us would undoubtedly occur did; and none of the ills that they claimed would be solved were.

For a diverse nation, we share a remarkable consensus with respect to educating children. As reflected in polls and focus groups, Americans are nearly unanimous in their commitment to certain fundamental ideals: that all children have access to a quality education regardless of family income; that they be prepared for happy and productive lives; that they be taught the rights and duties of citizenship; and that the schools help to foster strong and cohesive communities. These are the ideals of public education.

One hundred and fifty years ago, a band of dedicated reformers declared that progress toward those ideals was too slow and proposed that a new institution be created to more effectively promote them. Led by Bostonian Horace Mann, the reformers campaigned for a greater state role in education. They argued that a universal, centrally planned system of tax-funded schools would be superior in every respect to the seemingly disorganized market of independent schools that existed at the time. Shifting the reins of educational power from private to public hands would, they promised, yield better teaching methods and materials, greater efficiency, superior service to the poor, and a stronger, more cohesive nation. Mann even ventured the prediction that if public schooling were widely adopted and given enough time to work, “nine-tenths of the crimes in the penal code would become obsolete,” and “the long catalogue of human ills would be abridged.”[9]

I can only imagine that the ghost of Horace Mann is spinning his grave like a cornish game hen on a spit powered by a gas-turbine engine. Let’s forget Mann’s hyperbole and limit ourselves to the ideals in the first paragraph and answering the questions I asked above, which are touched upon in Coulson’s first paragraph:

Have public schools eliminated gangs? No, they’ve simply extended their reach from the streets into the schools in the same neighborhoods.

Have they prevented crime? Not even close. It’s why we now have cops (er, SRO’s) patrolling inner city schools, metal detectors at the entrances, and turf fights by drug dealers in the hallways.

Have public schools produced an educated citizenry capable of understanding complex issues in a pluralistic society? It is hard to even write the question without wanting to stop and laugh.

In other words, none of the “horrible hypotheticals” that helped justify compulsory state education have been eliminated. Conversely, none of the supposed benefits of the ideals of compulsory education have been achieved… And we’ve managed to flush several nations worth of GDP down the toilet in the process.

None of this even begins to address school shootings, the outsized influence of teacher’s unions, the continuous degradation of curricula, the college-loan debt fiasco that is a direct consequence of the “everyone must go to college” mantra, the millions of unfilled jobs in the skilled trades, and a list of horribles that are in no way hypothetical, but entirely real and ongoing. NOW add in the taxpayer dollars that have been poured into this bottomless money pit, and an honest person can reach only one conclusion: the entire experiment has been a complete and total failure and one that was entirely predictable. Blow it up.

This failure is just another example of what Friedrich Hayek and other economists of the Austrian and Chicago schools would have called the failure of central planning. The idea that a school guidance counselor, or any government official, knows whether or not your 12 year-old son or daughter should go to college for some particular future career a decade hence imputes a level of sagacity and foresight to that person approaching Godlike omniscience. It is just one among many laughable assumptions at the heart of the entire compulsory education system. It presupposes that social engineers in government are qualified to make qualitative value judgments about your child’s future career from their limited interactions with that child – and several hundred others, too. Worst of all, you – the parent – are a mere witness to all of it, lashed to that ship, in fact, pressured by our entire brainwashed society into accepting its false premises.

I recently learned a new word: introjection. It’s when you unconsciously adopt the ideas of others. I was reading a wonderful book by Anthony De Mello called “Awareness” and he suggests that a good test to tell if you’re brainwashed is by your emotional reaction to someone attacking an idea that isn’t your own. If you defend it reflexively, that’s a pretty good sign that you’ve been brainwashed.

Now ask yourself this: do the things I say about public education offend you? Do you find yourself reacting emotionally, defending the system of which you were a part? Did you think up the idea of public education yourself? Now ask yourself if public education is really as necessary as you think it is.

Even if one argues that it was a necessary service in the 1700s, or 1800s, or even 1900s because of a lack of access to information, scarcity of the written word, or any other factor, does any of that hold true today? Even the most unfortunate children in the country have access to all of the world’s information on a public library computer, or, much more commonly, in the palm of their hand.

The solution to this problem – and many others – will require the abolition of state schools and a completely free market in education, but teacher’s unions and their grip on the political class – or should I say the grip their donations have on the political class – will never allow that to happen, so it begins with school choice, an incremental approach that will return education decisions and tax money to parents. Will it solve the problem for poor people? Not initially, but as has already been demonstrated, neither has the public school system. It’s not a satisfactory answer, really, and I understand that, but what we’re doing isn’t just “not working,” it is a blight on the country and a national embarrassment.

Consider this, though: if I had told you in 1985 that people living in housing projects would have cell phones comparable to the richest among us, tools that would be able to do everything that Captain Kirk’s communicator could (except vaporize bad guys) and shoot professional quality video and photographs – it would have been laughably absurd. Yet here we are living in that reality through the miracle of (relatively) free markets. It is long past overdue for this Nation to give markets a chance to deliver on the ideals of education that the State and its staunchest advocates and defenders have promised for several centuries and spectacularly failed to do.

Q.E.D.

[1] Paul Lockhart, A Mathematician’s Lament, p.15

[2] Ibid., p.18

[3] This includes science. Most notable among compulsory state education failures is what has been done to degrade science and turn it into politics: “consensus” – where we ‘science’ by vote. Because the subject itself is so vast, ranging from the replication crisis to Karl Popper (and the Irrationalists) to Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, I request a bit of indulgence and leave it in favor of its own separate post, so that this piece does not bog down and detract from the larger, broader point about education.

[4] The movie depicts AOCS candidates, whom we would occasionally see during our training. They kept us segregated largely, I believe, so we didn’t ruin those kids with kindness. After all, just a few years ago that had been us during our last college summer, enduring the roasting humidity of Quantico, Virginia, at Marine Officer’s Candidate School. We had a lot of empathy for them – and we hadn’t been simultaneously trying to learn to fly a plane!

[5] Walker, Billy D. “The Local Property Tax for Public Schools: Some Historical Perspectives.” Journal of Education Finance 9, no. 3 (1984): 265-88. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40703424.

[6] From: Notes On Virginia. viii, 388. Ford Ed., iii, 251. (1782.), as quoted in The Jefferson Cyclopedia, a comprehensive collection of the views of Thomas Jefferson, Ed. John P. Foley, Funk and Wagnalls Company, New York, 1900, page 275.

[7] “From Thomas Jefferson to George Wythe, 13 August 1786,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 30, 2019

[8] Hat tip to my 1L Civil Procedure professor Mel Zarr, who first coined that phrase – and occasionally used it as a bludgeon against students. As in: “Ah. The old horrible hypo; without the position you’re advocating, the Republic will crumble.”

[9] Andrew J. Coulson, “Are Public Schools Hazardus to Public Education?” Education Week, April 7 1999, Vol. 18, No. 30

Christ, another officer? Who’s approving the applications around here?

This is what gentrification looks like.

I did not know Dale was a proper officer name…

Don’t you mean Officer Gribble?

Well i never watched whatever that is… so i can assume the article contained quotes

Not at all. That character is from King of the Hill, and was an anti-government conspiracy theorist. But it’s also the first character that pops into my head anytime I hear the name Dale.

John C. Reilly’s brother in “Step Brothers” – the wife hits me with quotes from that fairly often.

For me the first thing that pops up is tucker and dale vs evil

I imagine Dale Earnhardt hitting a wall.

I don’t trust anyone who made it past E-4.

You know who else didn’t make it past corporal?

Klinger?

Just recently re-watched the episode where he was promoted to sergeant.

Radar? (although there was that episode where Hawkeye made him a ‘corporal-captain’ so they could drink in the O’Club together.)

Ted Bundy?

The sham shield has the highest autonomy to responsibility ratio.

+1 E4 Mafia

Lance Corporal Underground >>>> E-4 Mafia

At ease Chipwooder!

Nuke it from space, dump the ashes in the deepest oceanic trench on earth. Case closed.

“You, sir, are correct!”

https://tenor.com/view/correct-sir-gif-13446407

You, sir, are correct also in stating it is an indoctrination center. A leftist indoctrination center, to be specific. Working like this is the only way those sub-humans can make any ‘progress’. When leftist just come right out and tell people what their intentions are, it scares the shit out of most people for obvious reasons. I mean it’s not often you get lefties as the dumb as the current batch (AOC, etc.) who just come right out and admit how stupid and evil they are.

Ozy, I missed you were a lawyer, too. What’s your practice?

Whoever will pay me. Seriously, I’m now back in private/solo practice, trying to get admitted here in AZ, whence the Missus and I recently moved.

Hopefully you don’t reside in the Phx metro area. Shudder.

West Valley – out in the desert, but they’re rapidly stripping that down for more neighborhoods near Bill Gates’ future ‘green city’ that will also be right near the freeway that’s going to run straight up to Vegas. I’m far enough out to be away from the stupidity, close enough for some of the ‘benefits’ of the city when I want to brave it.

Public school is the disaster it was meant to be. I am not sure it would have turned out better but the monster we deal with today is the child of Woodrow Wilson.

It’s older than WW. It’s a TR Era thing.

And TJ was it’s first presidential proponent, wasn’t he?

Excellent article. Every contact I have had with public education is worse than the earlier one. From the time I was a child to watching my grandchildren enter the maw. As parents we removed our two children in 7th grade through 12th from public education. We put them in Catholic Schools (though decidedly not Catholic) because they were the best educational institutes possible where the military sent me.

The best public ed we encountered was in a rural Montana school district west of Bozeman. California was scary to even contemplate and even the schools in the “Raleigh Research Triangle” area where pretty damn bad 19 years ago. I don’t even want to contemplate today. Out here in Hawaii it is well known sending your kids to a public school is damn near child abuse, so much so that Hawaii has the most flourishing system of private schools that I have seen.

I was in public school from ’68 through ’80, in small town Texas. In Jr. High and High School, there was only one school, so it was fully integrated. Discipline was probably about what it needed to be. I got a decent education, mostly because there was always one or two teachers who kept me engaged. There was relatively little fluff – it was math, English, some kind of history/social studies/civics, science. You really could only do one extracurricular at a time, so there was pretty much a full day of classes, with maybe one “non-academic” period per day. As an aside, I grew up with just about every kid my age in town, race, creed, income, etc. all in one place, which was a good education in itself.

IOW, probably about as good as it got in public school.

I had something similar but about a decade later and at a “bus the smart white kids to the ghetto” school. In its day it was highly-regarded, lots of corporate funding, etc. I hear it’s gone to shit.

I was part of the bus upper income Asian and white kids to the ghetto. Now we function as 2 schools within the school. We boost best scores but never interact with the ghetto kids because we are taking only advanced classes

All the Asian kids in my day were refugees from Cambodia and Laos – i.e. dirt poor. Great students, most of them.

“Discipline was probably about what it needed to be.”

You mean when you got home and told your parents that you got in trouble in school they would slap you upside the head and ask you WTF you had done, too?

Pretty much. There was the occasional paddling, detention also (pretty rarely). Detention was strict – you sat in the cafeteria under the gimlet eye of one of the teachers and did your homework – no talking. No lip or backtalk really tolerated, although they were totally indifferent to us smoking in the parking lot before classes and pretty tolerant of pranks, really.

Also, if you just had to fight, one of the coaches would take you and your opponent behind the school, give you both boxing gloves, and watch you go at it (with plenty of verbal abuse) until you were both crying. Nobody really wanted to do that twice, because they made sure there were no winners.

Money-wise we won’t be able to avoid sending our daughter to the local public elementary school for at least a few years, although thankfully it’s well-regarded. My plan is to try to get her into private school for middle school onward, hopefully. We’re not Catholic, but my wife’s family is so Catholic two nuns from Mother Theresa’s outfit flew over to attend her cousin’s funeral at her grandmother’s behest, so strings might could get pulled for a discount. Failing that, there are a few Montessori schools in the area, and I could always go back to the Episcopal church so I can get her enrolled somewhere with a golf team.

Sign the kid up for non-school activities, preferably activities where there the kids aren’t all the same age. The step daughter took French one day a week, and a dance class. When she was no longer interested in French, she tried Taekwando. Started violin lessons in 7th grade. The best part of all that was by high school she learned how to manage her time well and get through the bullshit subjects without much drama.

That’s really good advice. We’re trying to get her started with that sort of thing already. She takes swimming lessons once a week, and we’re going to start her in gymnastics soon.

Not good enough. Those don’t require any work on one’s own. French, dance, Taekwando, and violin all needed her to practice a bit on her own outside of class meetings. I forgot the wife had the kid in gymnastics – she wouldn’t sign her up again after the first 8-week thing because it seemed completely undisciplined.

I don’t know the age of your kid, so if she’s under 8 those swimming and gymnastics activities are probably fine. It gets her used to stuff outside of school, and then she will probably bore quickly if they seem like playtime more than skill time.

She’s 4 next month, so yeah, she’s well south of that. The swimming is her grandmother’s deal; she’s not that into it because it’s one-on-one drills with three other kids, so 75% of the time she’s sitting on the steps waiting to actually do stuff, but she is learning how to actually swim, which is important. She does soccer at daycare, but it’s really just kind of herding cats and hoping some of the drills stick.

It’s funny, she’s a really social kid for a (so far) only child, but she also doesn’t have a hell of a lot of patience for people, so she’ll try to get other kids or adults involved in doing something she wants to do and then move on if they don’t do it to her satisfaction.

She sounds like management material.

My condolences.

Damn, that soccer reminds me of little league. Not that I’m down on it, but most of the coaches meant well without having the faintest idea what they were doing. Mostly the kids just needed practice time with real baseballs and real bats, real catchers equipment and real fields. Someone to hit them grounders, fly balls, pitch to them, etc. But one coach was more interested in winning than giving the lesser players enough practice to get better, another was a little too into working with the kids (a la Kinko the clown). I had one coach who was absolutely great: he made sure the best kids only got two innings in an occasional game so they could see what it was like to ride the bench and he would not take shit from his own kids about sitting out even though they were very good players – and it kept the lesser players from whining to their parents about not getting to play. We could have won more games, but nobody complained and that was the most fun season I had in LL.

At some point the good players want to help the bad players get better and they help them at practice. For a lot of the bad players, they were bad for reasons out of their control: I remember one kid who’s father was blind. How is that kid going to get to practice with his dad?? If he’s not in a neighborhood with a bunch of kids a few doors away, the only time he really gets to play ball is at LL practice and games. A kid can practice dribbling a soccer ball and kicking at a makeshift goal, a kid can shoot baskets in the driveway by himself. The best baseball drill to do alone is to throw against a brick or concrete wall – which was common in my neighborhood but not so common in others. The garage doors in my neighborhood were all very strong – throw a wiffle ball at my garage door now and you’ll dent the thing. So baseball requires another person for practice most of the time, something I took for granted as a kid.

As an example of this — the CNA who helps take care of my dad (paralyzed from a stroke), has a daughter in high school, in one of the most awful Los Angeles Unified schools. She’s bright, but has very little choice in what school she can go to. For Christmas, my mom bought two copies of a book (I think it was Macaulay’s The Way things Work, but I don’t really remember, a book like it that has various explainer chapters on a wide-variety of topics), one for my son, and another for her. And this girl called my mom to thank her with such enthusiasm, that she read it twice, cover to cover, in a week, and had learned more from that one book than she had learned in her entire time at school.

That’s how badly we’re failing these kids. This is a girl with a supportive dad, eager to learn, no drug or gang problem that I’m aware of, and yet her school still did nothing for her. (and realize she’s going to graduate and so are all/most of her classmates, equally uneducated, because graduation rates are what matter, not learning, not achievement)

Almost all children are born with a joy of learning. Then the schools beat that joy right out of them.

I was one of those weirdoes who actually flourished in the schools as designed. But yeah, I’ve learned that not everyone is like that….

I did OK. Could have undoubtedly done better in a different environment, but between my parents (who simply would not accept anything but straight As) and a teacher or two every year, I think I had a leg up on a lot of people.

My problem in school was that I was generally bored shitless, so I would entertain myself by being a wise ass.

I had that problem in school. I had that problem after school too, but I had it in school.

I did great academically but had me some 15 suspensions and was always on a first name basis with the top men that ran those institutions. I was often told that my rebellious and anti-authoritative nature sullied my education record by these people, but I realize now that it was precisely my rebellious nature that kept me learning and wanting to learn things. I was otherwise bored out of my freaking gourd in class because it was too slow. Even the fact that my dad decided a way to slow me down was to send me to school with the locals in whatever country we were in (learn the language then smartass was his favorite thing to tell me) instead of the school the other American kids went to worked in my favor. I learned the languages but was always inclined more towards sciences, and that shows even today where I could care less if I am pissing off language majors with my abuses. I often also wonder how many people ended up doing poorly here in the US because our school system tries to pretend it exists and is a one size fits all system. No other country I attended school in did that. kids were tested and steered to an education appropriate to their intelligence as well as aptitude, with the whole system allowing even the slowest person to go all the way to the end at their pace.

I was otherwise bored out of my freaking gourd in class because it was too slow.

Yeah. Fortunately, I had some teachers who made allowances for me; they knew I was caught up on the curriculum, so if I sat through English class reading something else, they were good with it. There were always a few classes, though, where I just clock-watched and waited for it to be over. I generally passed my time in those classes helping other students cheat.

We moved from a big suburban school district to a tiny, more rural one (graduating classes of about 60) because two of my kids struggled at school. All of my kids did/are doing pretty well there. No fights, no gangs, and most of the kids and parents take school seriously. The biggest godsend we have is the two special ed teachers who worked with daughter #2. They went WAY above and beyond to help her succeed. (She is graduating in a few weeks). In that bigger school district, she would have been completely lost.

So, I think it all has to do with both the size of the school, and the community surrounding it.

What a great write up. And that graph….

This is a subject close to me. I have three kids, two of whom are “special needs”, meaning they struggled in school. So I know full well how the “one size fits all” mentality fails to help a lot of kids. At my job, I write software for schools, and most of what I do involves collecting and reporting data to the state, which is then used to determine how much money each school district gets. There are big, fancy buildings at every district full of well-paid employees who do only this. They are a big part of the blue and orange lines on the graph.

I do see some glimmers of hope, though. In our district, vocational classes are very popular and about half our seniors take them. We also have community colleges and local branches of Purdue and Indiana University nearby, and those are pretty popular too. I listen to a few popular podcasters who really push the need for a new direction for education. While there is still a lot of entrenched money and power, there is some change happening.

School choice is how the unraveling of the public school monopoly begins; but it has to begin with starving the beast. The funding and incentives around school, and its ties to politics, is what makes it so perverse and so hard to eradicate. You could get a sense of the level of desperation by the vitriol toward Betsy de Vos. But once that economic pipeline from property taxes to teacher’s unions is choked off, we’ll begin to see some relief.

That’s why I always couch it into Backpack funding whenever I bring up school choice. I don’t mention vouchers, private/public, any of that. Just that a school gets funding for every student that’s enrolled there. It mutes the standard counterattacks quite a bit.

I like to mention how interesting it is that people think monopolies are terrible, unless it’s a government-sector monopoly, at which point lots of people suddenly think the same monopoly magically becomes virtuous.

I’m going to push back on that graph a little bit. If you were do divide all of the kids up into various ethic groups. Each group has increased a little in performance. However the percentage of each ethic group has changed causing the flat lining of the overall performance. To be sure the increase don’t justify the large increases in outlays. Another confounding factor is how much of that cost is going to pensions. We’re an aging society and that messes up the finance of government on all levels trying to keep the elderly in the style to which they are accustomed to and promised.

I don’t see how the (potentially) changing ethnicity of the attendees really makes a difference.

Excellent point on the cost of pensions, though. I’d like to see the graph with that factored out.

I haven’t read the article yet, but wanted to introduce myself quickly and then I’ll read the article and perhaps join in.

I am a long time lurker over at HyR, though I spent the most time there around 2012-2014. I made a single post in all of my lurking years.

I stopped going for a few years as I changed careers (from accounting to teaching high school math) and was not in front of a computer all day. Recently have gone back into finance (I’d love to someday share my story of the hell that is public education). Anyway, I started following HyR again and my god, is it a shitshow. Luckily I knew of the exodus and have been lurking here a few weeks. It’s been like finding a long lost friend.

I have always felt a kind of intellectual loneliness. I’ve never quite fit in anywhere in terms of my worldview. It probably sounds silly, but I feel like I fit in here even though I’ve always been a passive participant. I hope that changes.

Anyway, it’s nice to finally actually say hi to ya’ll. Many of you have been a positive part of my life for years without ever knowing that I even fucking exist.

One last thing: Fuck Tottenham.

Test to see if I can post while my first comment is in moderation.

Welcome, Tulpa!

As both a former student and a former teacher, I can say that Ozy hits the nail square on the head.

When I graduated from Boston University in 1991 – damn you old

Back to reading article…

The wonderful thing about this comment is that I can laugh knowing you’re gonna get yours…

One way or the other.

He is not that old…

1. I am continually amazed by the people who write for this site. This is the kind of writing I would expect to see in an academic journal or long form policy journal. Honestly, I would not be at all surprised to find out one day that my dumb ass has been bantering back-and-forth with famous authors, thinkers, and experts in their fields, the knowledge of whose real names would shock me into embarrassed awe.

2. Your point about training is a great one. In my neck of the woods I see a lot of web developers with education but no training, which tends to make for lots of ex-web developers after a few months. In my case I had training without education. There were fundamental gaps in my knowledge that were problematic, but by and large the hands-on approach has served me well. Early on, in practical terms, I was better prepared than a lot of the new devs I see come through our shop, and the skills I developed through the process of self-teaching have helped me.

3. My wife taught public elementary school in Montgomery County, Maryland, for about ten years. The linked article about equity hits home, because even at that early age a lot of the effects described were in play. One of the things she used to say, and this seems to be a common complaint, is that she spent most of her time parenting other people’s children rather than teaching them. For a lot of those kids, school was the only structure they had, and their teacher was the most stable adult in their lives. This is emphatically not a point in favor of public schooling.

For a lot of those kids, school was the only structure they had, and their teacher was the most stable adult in their lives. This is emphatically not a point in favor of public schooling.

The best predictor of academic achievement is not money spent per pupil, or teacher pay, or classroom size, or facilities, or any of the other crap promoted by the education establishment. The best predictor of academic achievement is parental engagement.

Absolutely. There was also a huge, huge cultural difference. Of course Asian families, particularly recent immigrants, do extremely well because there’s a respect for authority generally and for teachers specifically ingrained in many Asian cultures. Better-off families of all backgrounds tend to do well both because there’s a parent with time to spend with their kids on homework, but also because those families typically have themselves valued education and pass that on to their kids. My wife found that African-American families tended to fare poorly because in her area many of them were coming from single-parent households where the parent of record was unstable, or was so busy with work that there just wasn’t anyone around to check on homework or even establish any real discipline. These tended to be the kids that were most challenging but responded best to structure; setting aside the kids who were destined for prison, the kids with the behavior problems often desperately wanted a stable, calm adult that they could trust and who would set consistent boundaries for them. Interestingly, contra what I’d heard and read, she said that the Spanish-speaking families weren’t much better. Similar issues as the African-American families, but added to that the language barrier and a weird sort of indifference to education. Some of the parents just didn’t see much point in school aside from free childcare since their kids weren’t making any money there.

My wife taught public elementary school in Montgomery County, Maryland, for about ten years…For a lot of those kids, school was the only structure they had, and their teacher was the most stable adult in their lives.

Did you mean any other county than Montgomery?

It’s funny how much of Monky County is an absolute shithole, but yeah, looking back on my time at Wiley H. Bates Middle School, located in the rather toney Murray Hills neighborhood of Annapolis, I distinctly remember a lot of kids who came from really, really fucked up homes. Turns out school can’t fix that.

The public education system in Roma ia post commie was surprisingly free of brainwashing in a political ideology sense. Although not in others… mist history had a statist bend and teachers generally expected children to blindly accept what they were told with a few exceptions. But actual politics was rare

.

I did have a history teacher who would low key say how the legionaires were misunderstood. And another who really hated hungarians…

While it is a great article and i agree with the premiss, i think public education would be among the last things the population would be willing to give up. Think of the children. Most people could not even immagine not having government schools

Many would agree they suck but that means we just need to make them betrer. Like everything else governme t sucks at. You would hear stupid phrases like baby and bathwater… its a good thing but misapplied.

Agreed. I think most people would put education in the same class as roads; something only the government can do.

I think you actually could pass some sort of voucher/school choice program, where the money follows the student. While that is an inferior outcome to full privatization, the idea that students and parents might be customers, rather than product, would be a huge improvement over the status quo. Moreover, such an approach might be a viable incremental step for the public’s fears to be put to rest.

It would be an improvement but to many think education needs to be government

I love that idea, but the argument that you’ll hear against that is that it leaves students who can’t relocate or commute sitting in schools that lose funding as better-off students leave for better schools, causing a death spiral of the schools that need the most support, i.e. money.

Except you don’t need to relocate or commute to go to a non-government school. They can be (and are already) opened anywhere.

But I can’t imagine a school that isn’t exactly like the ones already out there!

Of course, but private and charter schools are scams, you see, and they operate under no standards at all. At least that’s what I learned from noted education expert John Oliver.

“Why do we even need brick and mortar schools any more?” should be the reply.

Because few families have a parent at home during the day, anymore.

Yeah, RC, then let’s take the money from schools and pay for daycare. And let the kids explore and use the ‘Net and have a genuine free market in education. I wonder what might happen then?

I had to leave out much or I could have gone on forever. My true “A-HA” moment came when my youngest daughter moved with me to the west coast for her last 1.5 year of high school. I put her in a charter school, where a lot of the work could be done self-paced, from home on a computer. When I met with the principal, she ld me there would be ‘no lunch’ at the school. I said no problem and shrugged, then she added: “It’s the only way we can afford to be open. If we serve school lunch, we become subject to the mandates…” After asking what she meant, she explained that something like either 60% or 40% of school costs is in the lunch programs. (I can’t remember whether it was 40/60 or 60/40, I just remember that being the split, and I sat there with my mouth opened.) She just smiled and said, “I know. It was a shock for me, too.”

Hey Ozy, great article! This is one of my biggest interests, and you have treated it well. I definitely know what you mean about going on forever. One of my first articles here was a 4 parter on the topic. ( here)

I’ll make sure to read that one!

Wow! Just wow.

Gruel is expensive in the US. I blame the free market myself

Ozymandias, great piece. If it helps, I went through 13 years of Catholic school, and at no point was it brought up that the whole public schooling thing was started as an anti-Catholic thing.

And there is at least one vocational/tech center still around from the old days. The Willoughby-Eastlake school district (Lake County, East side of the Cleveland suburbs) still has a program in place for people. I’m not going to say all of the options they have should exist, but at least they’re trying to do something.

Meanwhile, my local school district (with dropping enrollment), just asked for an extension on a levy to pay for more renovations. Thankfully, I’ve got no kids that would be going through the schools.

“at no point was it brought up that the whole public schooling thing was started as an anti-Catholic thing.”

That’s because they were busy teaching rather than politicking.

Ask yourself why the media spends weeks on a single Catholic priest kiddie-diddling incident and barely mention (if at all) the weekly incidents of public school teachers fucking students.

I spent two years at the W-E Tech center. I was in the last “electronics” class to be taught how to fix tube type televisions. I have not taken the back off of a TV since I graduated.

So how was it there? I had friends who went to Willoughby South, Eastlake North, Lake Catholic, and I went to Notre Dame-Cathedral Latin.

I was done before the PC nonsense got rolling. My kids went through the W-E district and I could tell that a lot had changed. The teachers in my time would make fun of the kids that walked into class smelling like weed. Now they execute you for having a cig in your car. My grandchildren are just entering school. My kids haven’t complained yet, but that may be because they know what will start a rant.

Well hell, South got rid of their logo over the past year or so. When I was in High School, it was the black students who were fighting to keep the confederate flag and logo.

After asking what she meant, she explained that something like either 60% or 40% of school costs is in the lunch programs.

People should be hanged from lampposts (figuratively, Preet) for this. That is insanely stupid and evil.

Are you *gasp* LUNCH SHAMING?!?!?!?

That article causes school shootings.

sun butter and jelly sandwiches

I had no idea sun butter was a thing.

Is that when kids get made fun of for having Hydrox cookies instead of Oreos?

That doesn’t surprise me too much. If you look at public education policy a lot of it only makes sense if the objective is to provide daycare and meals on a subsidized basis to a community of children. When I was in high school in the late 90s you could eat breakfast, lunch, and dinner at school, although I believe the latter was based on household income. The assumption was that the school would be providing food for students who would not otherwise be able to eat at all that day. Naturally, this leads to some juicy contracts, and so you get a situation where state money is being funneled to private contractors who generate serious margins on food and service contracts. And since it’s free money from the district’s perspective there’s no real motivation to cut costs or to monitor quality.

Yahtzee! Funny how incentives work. And how much would you like to wager that some of the administrators might even have personal/fiscal relationships with the contractors?

Whatever are you implying? That various in-laws and cousins might have some common business to discuss over Thanksgiving turkey?

I remember the local rag published a story about how the same contractor who was providing food for the city jail also had the contract for the city’s public schools. The joke was that it was intended to keep the transition from the one to the other nice and easy.

“Naturally, this leads to some juicy contracts, ”

Naturally, it leads to those children growing up and thinking it’s totally normal that all their children’s meals are provided by someone other than the parent.

Crazy. When I was in Germany, there was no “food service” as such. You were let out at around 1PM and expected to eat dinner at home. They had a cart with bakery items and a vending machine with milk for the main 20-minute or so break between classes at around 11AM, that’s it.

*which you had to pay for out-of-pocket

Even before i knew i was a libertarian i was fascinated how school can take children so curious by nature and eager to learn and make them not want to learn

Great article Ozy. I have two girls in public school. With some regularity they come home and tell me about something absurd that happened at school that day. It may be lousy teaching, an administrative absurdity, or creeping politization of a topic. I start railing against public schools. They’ve gotten used to it.

My wife and kids know to avoid the subject entirely. Wife and I were somewhere and a couple brought up public education over dinner and my wife just sat back and laughed, and said, “Oh no. Don’t get him going.” I think the wife may have been a teacher. I’m patting myself on he back for entirely avoiding the subject of teacher’s unions in this article. I think I shoould get a “restraint medal.”

Fuck, my mom was a teacher (at the grade school I went to… I do not recommend that) and then a substitute teacher for years. Because of how long she was doing it, my parents are living on the pension instead of touching any of their retirement savings. It’s kind of funny to hear my dad complain that they have too much money, and don’t know what they’re going to do with it all.

*Sends Neph may bank account info*

I’m not planning on seeing any of it. I’m expecting them to spend it on themselves, and dole out any remainder to my niece and nephew. Besides, they’re both still active, and I’m not sure my dad has really looked into how much assisted living/nursing homes can cost.

I told Pater Dean last week that I would be very disappointed in him if he leaves us much of an estate. That money is for him and Mater Dean to enjoy; neither Bro Dean nor myself really needs any money at this point.

I said the same thing to my Mom many years ago — “I want you to die penniless after having spent all of your retirement savings on yourself.”

Sadly, she did not listen to me.

Donate to a NFP that actually educates children?

Excellent article, Ozymandias.

Remember kids it’s a government school not a public one.

I will recommend John Taylor Gatto books for anyone looking to get pissed about schools. He goes through a lot of the early reasoning behind compulsory education and it’s not for the public benefit (surprise!).

One highlight is the literacy rates dropping considerably after mandatory schooling is enacted. As found through the military testing.

We have homeschooled all our kids from day one and have seen many friends come into homeschooling for various reasons. Our latest conversion has a teacher as the mom. When my wife and her were discussing our curriculum and what we’ve gone over, she was blown away by the amount of books our kids read / have read to them and history that we cover.

Great article. I’m only halfway through, but will finish this later. Wanted to reach out to you while the thread was still live.

Reach out any time… just, you know, be careful where you touch.

Not one word about the evil that was John Dewey?

Feel free to add on! I’d love to read something you write on him, HM. Seriously. There’s just so much there to hate!

What Dewey really meant by “the purpose of schooling is socialization” could be a blog of its own.

Well, I’d say that there was something to that. After twelve years of public school, I was thoroughly repulsed by mobs of my peers and the idiotic demands they’d place on one another. But, I don’t think that was what Dewey had in mind.

Dewey was a shit stain retread of Mann.

It’s always the same disease:

“we know better than thee and we’re going to jam it down thine throat… for thine own good, of course. And by “thine own good” we mean, “via ‘society’s good’… and you reap all of those unseen benefits. So, just hand over thine coinage and shut the fuck up.”

Oh, they were certainly cut from the same cloth. But, Mann, at least saw public schooling as a way to “preserve” civil republicanism, which he supported. Dewey, on the other hand, saw it as a way to destroy civic republicanism, which he saw as the great obstacle to his social democratic utopia.

Dunno who dat iz but a quick google brings what an asshole to mind

I was just watching soph’s “Be not afraid” video on YouTube, and it was removed as “hate speech” when I was about 2/3 through. They haven’t banned her account yet, but I imagine it’s just a matter of time.

If public education was better soph would be more smarter

And she’d know her place.

Alternate Channel – direct from her twitter a few minutes ago.

Alternate Channel — This is from her twitter feed a few minutes ago.

Alternate Channel — from her twitter feed.

Sorry Oz, don’t have time to read it now but I will later. Looks like it will be good.

Greetings to everyone else from a Waffle House in Fayetteville, Arkansas.

I am at a irish pub close to my house drinking pilsner urquell pint and watching cricket. For the life of me i cannot understand it. Also i comment on my phone and assume I make a ton of spelling mistakes

Say hi to Flo for us.

I’ll hang around here for a few days and check back in to answer, so no rush, Scruff. Have a waffle for me and put lots of syrup on it.

No sugar is bad

I know, Pie. It will be the subject of a future piece, but some maple syrup on a waffle every now and again won’t kill one… especially since he was the one eating it and not I!

Smothered and covered!!

I don’t think that was ever the true goal.

I thought the stated goal was creating people capable of working an assembly line in a factory

I reckon we do need some form of public education for such reasons (even though factory workers are a thing of the past). That is, to be functional economic beings.

But education has become bigger than that now given all the ideological nonsense. They seem to want to produce little tyrannical tikes incapable of free or independent thought. Worse, they seem to want to destroy it.

People will need some severe deprogramming. Heck, even among by circle of friends they don’t realize how much shit the system filled their heads with.

They seem to want to produce little tyrannical tikes incapable of free or independent thought.

And why shouldn’t they? What are the parents going to do? The union represents a major political constituency for local politicians, so it’s not like the school is going to do anything.

ChipsnSalsa gets it…

There’s no question the public education model in North America is obsolete now. It will eventually collapse but not before teacher’s unions are weakened – which I’m guessing will happen at some point. You can’t keep pushing a narrative with such poor results and expect it to claim ‘all is well!’

“When I graduated from Boston University in 1991,”

I hope it was better pre-AOC. /Lionel Hutz shudder.

“To wit: when the last President was running for his second term, I had three daughters in high school together. ALL of them were mandated to read a sitting President’s autobiography and write a paper about it; the oldest would be eligible to vote in the upcoming election.”

Disgusting. Especially the part where ‘independent thought control’ punished one of your daughters who dared to challenge and question authority.

“and schools instead became college-entrance mills, a pipeline for everyone, regardless of aptitude or even desire, to go to almighty college”

That’s how it was for me while in high school in the 1980s. Go to university because employers will demand a degree – doesn’t matter what – just get a degree. The whole thing left a cynical taste in my mouth. I don’t know even know where my diploma is to be honest.

“By the time I was in high school in the mid-80’s, society had almost gotten to the point where we are now – where anyone who didn’t want to go to college was considered somehow a less than.”

That happened to my buddy. I remember him being chastised by a chemistry teacher because of his apparent lack of interest in the periodic table. He asked him what he wanted to do in life and my friend said, ‘an electrician like my father and to eventually move to the USA to make real money’. The teacher literally mocked him and told him was he was going to be dumb if he didn’t get that degree. Well, old Johnny boy did become an electrician (and a damn fine one) and took off for Florida and then North Carolina and then back to Florida. He’s never looked back and enjoying his life.

“that the Germans first established the public funding of compulsory education.”

The Germans invented the progressive movement. A populace very vulnerable to being deferent to authority (particularly since Bismarck) so it makes sense. Every time I read progressive stuff I read it in German.

Great piece.

I’ll bet a million bucks your friend’s making much, much more money and enjoys his job more than that teacher.

Not only that. He married his high school sweet heart. Straight from our hood.

Yeh, he ain’t coming back.

“Do you know why crime is so low in Germany? Because it’s illegal.”

I tell that joke to my friend who was born and partially raised in Germany then emigrated here – and she laughs her ass off every time. Then tells the story of how she got a jaywalking ticket at 1 am by crossing against the “Don’t Walk” sign – with nary a car within miles. The officer was quite earnest that she had ‘broken ze law.’

So it’s not surprising that ‘ze Germans’ (Germanic culture) gave us this.

Marx wasn’t Spanish, after all.

OT: Dorf is dead. A true genius has been lost.

“Leonard you hooked it into the 220!”

Sad

Apple Dumpling Gang is still good comedy.

Oh man, I loved both Apple Dumpling Gand movies when I was a kid.

Thirded. Perhaps that is the transmission vector for Glibness?! I need funding to study this.

+1 infected here too

Oh, man. That sucks, but he gave us a LOT of laughs. We used to watch the “Carol Burnett Show” as a family. I loved watching Harvey Korman trying to hold it together while Conway was… being Tim Conway in character.

Damn. I tell ya, that Burnett crew….pure comic genius.

Well, shit.

One time when I was younger, I overheard a conversation by a couple people who were teachers. They were discussing the merits of different educational models. One was advocating a replacement of the traditional public school model with a newer one. It replaced the old factory assembly line model with newer production team techniques. It was then I realized one of the biggest problems with public education. They saw the student as the product, not the customer. In a free market educational system, the school is a service provider and the students and parents are customers. And the incentives run accordingly.

I’ll give just one example. When I was young, I was hopelessly unathletic and absolutely hated gym class. Hell, one of the gym teachers had even threatened to beat me up (to this day, I still don’t know what that was about). It wasn’t until I’d reached adulthood and went to an actual gym where I was a customer that I had any interest in fitness encouraged or supported. It was really night and day.

They saw the student as the product, not the customer.

Your customer is who pays you. Government schools have no customers, except the government. Students, under current funding rules most places, are fungible Meat-Based Funding Units.

who generate more funding when classified with some sort of learning disorder.

Students, under current funding rules most places, are fungible Meat-Based Funding Units.